The implementation of the EU Nature Restoration Law

This article analyses the upcoming implementation of the Nature Restoration Law (NRL) based on current knowledge, from the perspective of ecological sciences. The EU regulation on nature restoration came into force in 2024. The official German legal term for the EU law is Wiederherstellungsverordnung (WVO). Central aspects are presented and the given roadmap for implementation is described, starting with National Restoration Plans (NRP), which Member States must submit in draft form to the Commission by 1st September 2026, following a mandatory participation process. Cross-references to other legal obligations at a global, EU, and national level are also analysed. These result in opportunities for a wide range of synergies, provided that appropriate sector coupling is implemented legislatively and practically through legal adjustments. It also becomes clear that effective implementation depends equally, among others, on: (1) an overall ambitious framework in the NRP; (2) a consistent move away from environmentally harmful subsidies; (3) the provision of specific financial resources in sufficient quantities, and (4) on the motivation of landowners and land users to participate in implementation through economic incentives. Submitted on 18 December 2024, accepted on 23 February 2025.

von Rainer Luick, Eckhard Jedicke, Thomas Fartmann, Manfred Großmann, Pierre L. Ibisch, Thomas Potthast and Josef Settele von 10.1399/NuL.119483 erschienen am 02.04.2025Dieser Beitrag ist auch in deutscher Sprache verfügbar: www.nul-online.de, DOI:10.1399/NuL.119461.

1 Introduction

The EU Nature Restoration Regulation (NRR) came into force on 18 August 2024 (EU 2024). The official legal designation is ‘Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on the restoration of nature’, or Wiederherstellungsverordnung (WVO) for short in German. In just over a year, by the deadline of 1 September 2026, EU member states will have to submit a draft of their national restoration plan (NRP) to the Commission as a first step towards implementation.

Building on an analysis of the technical and European policy background and the process of developing the NRR and the key players involved (Luick et al. 2025 a), this article analyses and evaluates the law by addressing the following questions:

- What is the schedule of the NRR and what specific steps will be taken to implement it?

- What differences in content and objectives, illustrated by the example of the forestry sector, have arisen after the trilogue outcomes compared to the European Commission’s original version of the draft legislation of 2022?

- In what ways is the NRR linked to other legal obligations? Do synergies or new lines of conflict arise from these?

- Which issues regarding the technical, legal and financial consequences of the nature recovery plan need to be clarified as a matter of priority?

Ultimately, the question is whether the NRR, as adopted, is an acceptable compromise and a sufficient and binding legal basis for the necessary changes. Or have the demands originally formulated been watered down to such an extent that meaningful action is unlikely and the result will simply be new bureaucracy and reporting obligations?

2 Key areas of action, open questions and a roadmap for implementing the NRR

The core element of the NRR (EU 2024) is formulated in Art. 1 with the aim that, by 2030, restoration measures must be taken on at least 20% of the EU’s land and see areas with ecosystems referred to in Articles 4, 5 and 8 to 12 (see below) where vital functions are not in good condition. By 2050, measures should address 100% of ecosystems in need of restoration. The NRR, as it has come into force, names seven fields of action (Fig. 1), supplemented by the obligation to plant 3 billion trees in the EU (Art. 13). The targets are shown in Fig. 2a and 2b along the time axis.

1Where the sites concerned are those containing habitat types defined in Articles 4 and 5 that are in a poor condition, restoration measures must be implemented on 30% of the sites by 2030. From a formal legal point of view, based on the definitions of the EU Habitats Directive, this refers to habitat types that are in an unfavorable-inadequate condition and an unfavorable-bad condition. This currently applies to more than 80% of the habitat types (see also CEU 2024, Luick et al. 2025 a). By 2040, restoration measures should then be in place for at least 60% of the areas, and by 2050 for at least 90%. Much remains unclear about the numerous possible exemptions, which would then involve modified implementation targets. In particular, the objectives formulated in Articles 1, 4 and 5 of the NRR contribute to the implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF), to which the EU committed itself at the 15th Conference of the Parties to the CBD (UNEP 2023):

- at least 30% of land and inland water areas and 30% of the marine areas belonging to Member States must be placed under legal protection;

- of which at least 10% of land and inland water areas and at least 10% of marine areas must be placed under strict protection.

These goals are almost identical to those of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 (EC 2020, EC 2022 c):

- statutory protection of at least 30% of the EU’s terrestrial area and 30% of its marine area and the integration of ecological corridors as part of a trans-European network of nature protection areas;

- strict safeguarding of at least one third of the EU’s protected areas, including all remaining primary forests.

The aim of the NRR is therefore simply to fulfil Europe’s and the world’s existing obligations. These also include pledges made to the EU which are to be implemented nationally in order to achieve the 30% protected area target of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 in the respective biogeographical region. The focus here is on Natura 2000 sites, supplemented by ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs; see EC 2022 c). It is still unclear how and when Germany will comply with this reporting process.

European Natura 2000 sites cover approximately 18.6% of the land area and are divided into around 26,000 protected areas. In Germany, there are about 4,500 Habitat Directive sites (special areas of conservation, SACs) and 742 bird protection areas (special protection areas, SPAs), which partly overlap; in total, these cover about 15.5% of the land area and about 45% of the marine area (BMUV 2024 b).

The area targets of the NRR are the subject of intense debate; they are interpreted in very different ways by lobby groups and in specialist circles:

- Does it mean only those habitats listed in the NRR and mapped in the standard Natura 2000 areas that are in an unfavorable-inadequate or unfavorable-bad condition? Or is it rather a matter of the total areas in which the habitat types occur? To a considerable extent, these also lie outside designated Natura 2000 areas and have been insufficiently mapped or not mapped at all, both in Germany and in other countries. This applies in particular to non-priority grassland and forest habitat types in Annex I of the Habitats Directive and the NRR with a large area of distribution; only a few federal states undertake meadow mapping consistent with the Habitats Directive. In addition, the more common habitat types are underrepresented in German Natura 2000 areas compared to the rare ones (see Friedrichs et al. 2018). At least the explanatory memorandums on the rationale of the NRR (EC 2022 a, b) indicate that the measures initially cover 30% of the total area of each habitat type (open land, forests, inland waters and marine areas) where there are deficits.

- Art. 4 para. 4 stipulates that restoration measures for Annex I NRR habitat types are also required in areas where they are not (or are no longer) undertaken. The logic is that the re-establishment of habitats is necessary to achieve a favorable overall site for a habitat type. For this target category, measures must be taken for at least 30% of the additional areas by 2030, for at least 60% by 2040 and for 100% by 2050. A look at the reporting, including the EU Birds and Habitats Report (BMUV 2020) and the Prioritized Action Framework (PAF) for Natura 2000 in the period 2021-2027 (BMUV 2025), helps here: These sources show that the entity ‘favorable overall habitat area’ has so far existed only as a qualitative estimate. In the case of forest ecosystems, significant areas for restoration are to be assumed, since more than 50% of the remaining forest area in Germany is dominated by non-natural coniferous forests that have developed at the expense of original habitat types. The relevance of this point is underlined by the poor condition of these forest areas and the corresponding plans and need for forest conversion. In any case, consistent quantitative and biogeographical data for an assessment are not currently available. It therefore remains unclear in which specific individual areas measures are required. The situation is exacerbated by the rapidly progressing anthropogenic climate crisis, as original and potential habitat distribution areas already differ greatly. The future emergence of new climate conditions and presumably new habitats raises fundamental questions to which there are not even rudimentary answers (see also the discussion in Section 6).

- Another (politically based) interpretation of the area targets could be that the percentage targets (30% by 2030, etc.) are derived first from the restoration plans and then aggregated from all measures in the areas addressed in the NRR (forest, open land, seas, floodplains, freshwater ecosystems and their associated habitat types). However, given the lack of sufficient spatially explicit data, the national recovery plan is unlikely to be able to achieve this within around a year.

From a legal point of view, Brandenburg’s recent decision to provisionally halt the NRR on the grounds of ‘a lack of legal guidelines at both the EU and federal level as to how this regulation should be implemented in practice’ (MLEUV 2025) is to be viewed critically and rejected from an expert point of view. Since the NRR is directly and bindingly applicable under EU law (Luick et al. 2025 a), neither the federal states nor the federal government can override it. Although Brandenburg is committed to the rapid creation of the necessary European and federal legal conditions, its decision sends a fatal signal, which has already been taken up by the Association of Family Businesses in Agriculture and Forestry, for example, with the demand for a withdrawal or at least a fundamental revision of the NRR.

In Articles 11 and 12, further non-site-specific measures with general objectives are required for agricultural and forestry ecosystems, in addition to the habitat types defined in Articles 1 and 4 (see Fig. 2 b). In this context, climate change, social and economic needs in rural areas and the supplier functions of agricultural and forestry products should also be taken into account. The success of measures should be determined by indicators, although the methods and the area to which they apply (e.g. country, region) are still largely unclear. The following indicators and an index derived from them are planned for agricultural land: (1) species of field birds; (2) grassland butterflies; (3) proportion of agricultural land with high-diversity landscape features; and (4) stocks of organic carbon in mineral arable soils. The indicators for forest land are: (1, 2) standing and lying deadwood; (3) proportion of forests with non-uniform age structure; (4) forest connectivity; (5) proportion of forests with predominantly native tree species; (6) tree species diversity and (7) stocks of organic carbon (see also Section 3 and Fig. 2b below).

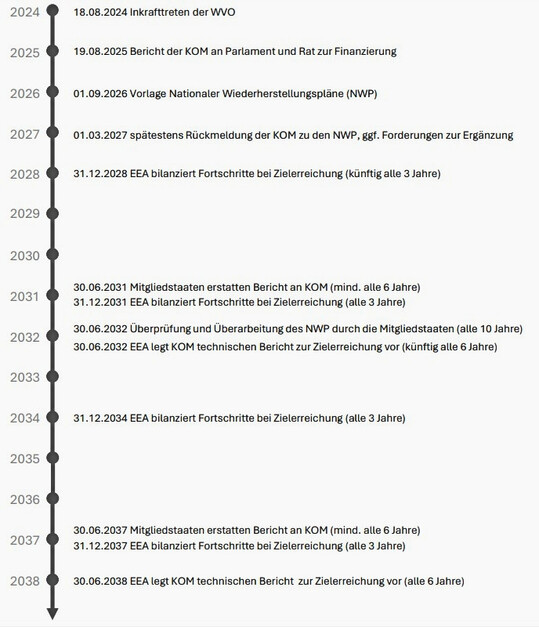

The main instruments of the NRR are the National Restoration Plans (NRPs) and the application of the indicator sets described for certain land categories as part of the reporting process (see below). The following key targets in the implementation and reporting schedule (Fig. 3) are planned:

- Each Member State shall submit a draft NRP to the Commission by 1 September 2026 in accordance with Articles 14 and 15 of the NRR. The NRP must be developed openly and transparently with the participation of the public and all relevant stakeholders. The following issues are to be addressed: – The NRPs should be based on the national context and take into account regional diversity. – Targets must be set for the years 2030, 2040 and 2050. – The necessary financial resources and the planned financing methods are to be clearly stated and accounted for. – Expected benefits and synergies with other policy areas (including on climate change, renewable energies, soil protection, agriculture and forestry, fisheries) must be clearly stated.

- The Commission shall assess the draft NRP within six months and, if necessary, request amendments.

- Each Member State shall review and revise its NRP by 30 June 2032 and again by 30 June 2042. Thereafter, Member States shall review and revise their NRP at least every ten years.

- In accordance with Article 21 of the NRR, the European Environment Agency (EEA) shall submit a technical overview of progress towards achieving the objectives and fulfilling the obligations under the NRR to the Commission by 31 December 2028 and every three years thereafter. The EEA shall also submit a technical report to the Commission on the progress made in achieving the objectives and fulfilling the obligations set out in the NRR, based on national data, by 30 June 2032 and every six years thereafter. In addition, the Member States shall submit data and information to the Commission by 30 June 2031 for the period up to 2030 and at least every six years thereafter regarding: – the national NRPs, – the location of any sites hosting habitat types or species habitats that have significantly deteriorated, – a description of the effect of remedial measures, – the results of monitoring (pursuant to Art. 20 NRR), – the restoration measures carried out (type, location and dimension), – the required financing, including a review of actual investments compared to the originally planned investments.

- By 19 August 2025, the Commission is to submit a report to Parliament and the Council on financing, which – identify the financial resources available for implementing the NRR and its realization through restoration plans, – highlights financial gaps, – presents proposals for bridging these gaps, also with regard to the multi-year financial framework from 2027.

3 NRR text and indicators using the forestry sector as an example

The guidelines for the forestry sector are already clearly specified in the NRR. In the online supplement to this issue, web code NuL2231, the key content from the original legislative proposal is compared with the negotiated wording in the adopted law. Furthermore, the eight indicators defined for the forestry sector, which are intended to demonstrate improvements in biodiversity in forest ecosystems in the member states in accordance with Art. 12 and Annex VI NRR, are presented in detail. For example, according to Art. 12 (2), an upward trend in the index of common forest bird species must be demonstrated. The Member States must provide evidence of an upward trend for at least six of the remaining seven indicators (para. 3).

At first glance, the changes made to the legislative proposal appear to be of little significance. Indeed, compared to the original proposal, only a few topics and demands have been dropped. This applies not only to the forestry sector, but also to other areas of application, and indicates that the negotiation process was not so much about substantive changes as about fundamental rejection or approval. Thus, only a close reading reveals the paradigm shift that occurred in the negotiation process: obligations and objectives that were mandatory have become discretionary, and the obligation to implement the NRR on private property has been almost completely removed.

4 The NRR as instrument for implementing and effectively reinforcing other legal obligations

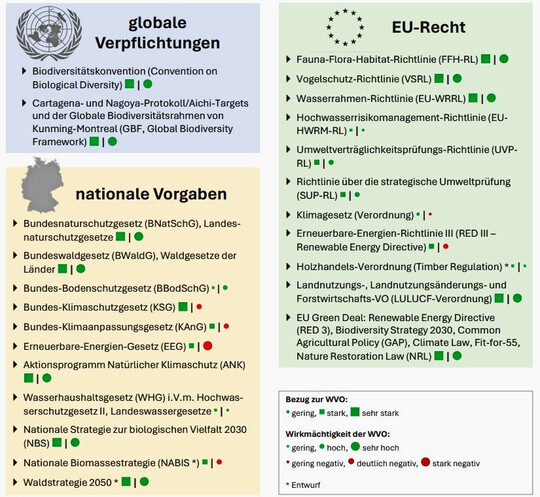

The significance of the NRR must be placed in a larger context and it will develop as an effective instrument not only through its own implementation, but above all through the consideration and strengthening of requirements in other legal areas. Fig. 4 provides an overview of the numerous legal requirements (laws, ordinances, internationally binding conventions) and political frameworks (strategies) at the global, EU-European and national German level that have direct or indirect imperative relevance for the NRR (links to the original documents can be found in the online supplement to this issue under web code NuL2231). These stem not only from the fields of nature conservation and the protection of biological diversity, but also from the fields of climate protection and the expansion of renewable energies.

The NRR is essential for achieving our goals in areas of activity that are crucial for our civilizational survival (see Luick et al. 2025 a). With one exception, namely climate protection and renewable energy laws, the legislation has at least a positive and reinforcing effect. In the case of the exception mentioned, the norm at the European and German level is defined such that the combustion of wood is generally still considered a CO2-neutral and thus climate-friendly energy resource – which has been refuted scientifically (for an overview, see Luick et al. 2022). It is planned that wood-based biomass will form an important part of all sectors (heating, electricity and fuels), playing a substantial and increasing role in achieving climate neutrality by 2045. This is particularly problematic in view of the fact that, due to the ongoing loss of forest area and deterioration of forest vitality due to overuse, forests in many countries have now become a source of greenhouse gases (GHG) instead of acting as a sink (see, for example, data for 2000–2023 and interactive maps: https://ctrees.org/jmrv). This also applies to Germany and has been confirmed by the findings of the fourth National Forest Inventory (BMEL 2024). Furthermore, the accounting of GHG sources has so far only taken into account the decrease in forest growing stock, not the emissions from soils.

Much of the loss of biomass and carbon in German forests is due to the direct combustion of wood, which accounts for approximately 50% of the total annual timber harvest, including a significant proportion of wood that is burned immediately after felling without any further intermediate use. This primarily involves burning wood in combined heat and power plants and in large power plants for electricity production. If this norm remains in place, the pressure on European and German forests will continue to grow and the urgently needed improvements to (forest) ecosystems will remain low-priority despite the legislation (see also Luick et al. 2025 b on the existing ecosystem services and resource capabilities of global, European and German forests in the face of climate change, in the following issue).

In order for the NRR to achieve effective results as quickly and unbureaucratically as possible, solutions must be found that do not merely follow the stipulations and objectives of the NRR as an independent project with its own program, methodology and administration. Rather, synergies and impact enhancements (sector coupling) must be promoted in the context of existing obligations and legal possibilities, along the lines of the wording of Article 14 of the NRR, which includes a request to this effect (see Fig. 4). To this end, an effective ‘restoration policy’ must be implemented, for which the German Advisory Council on the Environment, the Scientific Advisory Board on Biodiversity and Genetic Resources and the Scientific Advisory Board on Forest Policy have identified central instruments (SRU, WBBGU & WBW 2024). Due to the land area involved, the potential knock-on effects and the issue of social acceptance, management systems must be identified, developed and promoted, particularly in the agricultural and forestry sectors, that provide objectively measurable services to fulfil the NRR target (see also Box 1). The following instruments would be particularly suitable for this purpose:

(1) The Federal Action Plan on Nature-based Solutions for Climate and Biodiversity (ANK), including its funding guidelines, is committed to the stabilization, restoration and preservation of ecosystems such as forests and moors in order to reduce GHG emissions and maintain sinks. The funding guideline ‘Climate-adapted Forest Management PLUS’ supports, among other things, the continued enrichment of deadwood, natural forest development, the reversal of drainage measures and the retention of deadwood in disaster areas. This is directly related to the obligations arising from the NRR, which must be made even more explicit when the ANK is further developed, particularly with regard to the interfaces between the areas primarily affected by the NRR.

(2) (2) The tasks resulting from the EU Water Framework Directive, which for decades has produced far too little concrete action (for the serious failure to meet targets as of 2021, see UBA 2022 a, b), could be significantly promoted by the NRR.

(3) A reorientation and appropriate programmatic focusing of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), both in terms of the framework set by the EU and in terms of national and, in the case of Germany, federal implementation, would be a decisive key to achieving the objectives of the NRR. Among other things, the following options exist, which in our view must be rigorously pursued: :

- Large-scale renaturation of floodplain landscapes, which is necessary for reasons of flood protection, to limit greenhouse gas emissions from intensively farmed organic floodplain soils and in accordance with the EU Water Framework Directive;

- Rewetting of organic soils in degraded peatland;

- Protection of existing carbon stocks in soils by refraining from and prohibiting negative practices such as unadapted land use, drainage or ploughing;

- Creating incentives for practices that rebuild carbon stocks – such as long-term species-rich (pasture) grassland (Bai & Cotrufo 2022), paludiculture, groves in open landscapes and urban areas such as agroforestry and hedgerows, new forest planting and timber harvesting with high-quality material uses; promotion of permanent measures for carbon enrichment in arable mineral soils (including humus-building crop rotation, introduction of biochar);

- Reintroduction of mandatory set-aside on at least 4% of arable land;

- Programming of funding elements in the second pillar of the CAP (amendment of the National Strategy Plan) and in the Joint Task for the Improvement of Agricultural Structures and Coastal Protection (GAK) from as early as the 2026 funding year, allowing targeted co-financing of NRR measures;

- Forest management measures and practices that result in verifiable carbon-storing and biodiversity-promoting effects in forest stands and soils (see also text box);

- Expansion and stabilization of wilderness areas that are permanently set aside (already funded in federal state programs and in the ANK funding program ClimateWilderness). Areas that are in theory no longer used, such as ‘non-managed production forest’ (W.a.r.B.) with a theoretical usage potential of < 1 m3/ha/year, in addition to the so-called NWE5 areas, the 5% of Germany’s forest area that is to be left to natural development in accordance with the National Strategy on Biological Diversity (BMUV 2024 a). However, it is important to note that the promotion of natural forest development without predetermined outcomes should not be limited to these areas;

- Integration of necessary measures to achieve the targets of the LULUCF sector (details in Luick et al. 2025 b, submitted).

- Integration into as many existing and strategically similar planning processes as possible (including management plans for Natura 2000 sites and the establishment of wilderness areas as a component of the National Strategy on Biological Diversity, NBS).

Experience gained from implementing Natura 2000 management plans and the water management plans resulting from the EU Water Framework Directive shows that

(1) there is always a long delay before such plans are implemented,

(2) they are often insufficiently binding, clear and implementation-oriented, which

(3) means that only a very few planning elements are actually realized. Failure to comply with or problematic application of directives, as in the case of relevance tests, can also lead to them becoming ineffective.

According to the fourth National Forest Inventory (BWI 4; BMEL 2024), 48% of Germany’s forest area is privately owned (of which around 25% is in small-scale and fragmented ownership). In our experience, restoration measures on private land can only be implemented in both forest and open land if convincing ‘joint participation offers’ are set up. Using the example of private forests, we present possible options to supplement existing programs:

- Promoting innovative forms of community-based forest management for the common good in which non-forest owners can also participate. This includes – carbon forestry models including set-aside and timber harvesting models that take into account long-term carbon storage targets for wood products, and – historical, traditional forms of forest management such as coppice forests, plenter forests and wood pastures (semi-open pastures).

- Restoration and development of resilient forest ecosystems via tendering procedures (offers) to forest owners based on expected minimum requirements. This can help to mobilize areas that have previously been inaccessible or difficult to access, and it generates useful ideas that go beyond those prevalent in the current funding landscape.

- Promoting civil society and entrepreneurial initiatives that mobilize additional resources and areas for ecological forest development. Firstly, this requires knowledge-based criteria to ensure the quality of such measures and to exclude counterproductive greenwashing projects (there are so-called ‘climate protection projects’ – some of which are supported by state forestry departments – that plant trees on sites where deadwood and pioneer vegetation have been cleared and the soil has been intensively tilled, thus undermining both the idea of climate protection and restoration). Secondly, incentives should be created that offer innovative forest owners and companies opportunities to contribute systematically and productively to the stabilization, restoration and preservation of ecosystems. In the context of climate protection, the idea of the ‘contribution claim’ has been developed (Kreibich et al. 2024), whereby companies support climate protection projects without crediting the emission reduction to their own balance sheet. It would be logical to further develop corresponding concepts with a broader ecosystem claim. Incentives for companies arise in this context from sustainability reporting requirements (in particular the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive; EU 2022); they could be further increased, among other things, by government recognition.

- Many programs to promote resilient forests are undermined by excessively high populations of hoofed game, which are a consequence of forestry and hunting strategies and structurally poor forests. In the future, funding programs must be linked to appropriate wildlife management, with effective impact monitoring playing a central role. It must also be possible to reclaim funding in the event of failures that can be shown to be due to poor management.

5 A critical reflection on the NRR – legal, ecological and financial aspects

On the international stage, both the EU and the individual EU member states generally advocate strongly for environmental concerns and sign binding commitments to that effect. However, when it comes to their own national actions, these commitments are often not met, and even obligations under international law are only implemented with difficulty, with long delays, only partially or not at all. This behavior in the area of land use and environmental policy has recently been criticized by the EU Court of Auditors in its evaluation of the CAP (ECA 2024). The SRU, WBBGR & WBW (2024) also note that ‘at the national level, setting the course for an ambitious renaturation policy is (...) a central challenge that is still insufficiently recognized by the public’.

The NRR formulates a central task for society as a whole, the implementation of which can and must make essential contributions to ensuring our future viability in the face of an ecological polycrisis (see Luick et al. 2025 a): The fact that nature conservation should long since have been understood as a fundamental protection of humankind and as a question of ‘survival ecology’ (Gardner & Bullock 2021) indicates the extent of the paradigmatic challenge. In implementing the NRR, eight areas of action are to be addressed, based on the brief critical reflection on the NRR that follows:

Action 1: Adapt legal implementation instruments, achieve synergies between different policy objectives

It is undisputed that implementing the NRR in Germany requires extensive adjustments in numerous specific laws at the national and federal level and the associated legislative implementation instruments. In addition to the actual environmental laws (Federal Climate Protection Act, Closed Substance Cycle Waste Management Act, Federal Water Act and Federal Nature Conservation Act), this also includes the complex legal systems of the agricultural, forestry and planning sectors (including building law, zoning, landscape planning). The time required for the parliamentary and legislative processes involved in amending the law is hard to estimate, especially in view of the current political upheaval at federal and state level. It thus remains uncertain whether the necessary legal adjustments (and, ideally, harmonization and administrative simplifications) will be implemented to any significant extent. At the very least, it will take a great deal of patience before the NRR becomes fully effective. It is precisely because of the potential synergies and interactions with other legal norms described in Section 4 that it is of the utmost urgency to tackle these tasks.

In addition, the NRR also contains inherent defects that virtually invite delays. Examples of this are given below.

Action 2: Clarify how to deal with the ambitious schedule

The timeframe for implementation with the adoption of the law in 2024 and the integrated setting of deadlines and targets for the achievement of initial recovery objectives by 2030 (establishment of national recovery plans and binding targets for recovery, see section 2) are more than ambitious. Even well-meaning actors are overwhelmed by the urgency, especially if Article 14 (20) NRR is taken seriously, that ‘the preparation of the recovery plan is open, transparent, inclusive and effective and that the public, including all relevant stakeholders, are given early and effective opportunities to participate in the preparation of the plan’. These consultations must meet the requirements of the EU’s Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Directive.

The deadlines can only be met by developing an initial framework and then progressively refining it in the period that follows; the required stakeholder participation must not be neglected in the process.

Action 3: Establish meaningful baselines and define targets based on them

In this context, the question of which baseline the restoration of ecosystems should aim for remains unanswered. For areas with habitat status, it is presumably the reported status from the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, this is already obsolete due to incorrect reporting at the time and the subsequent effects of climate change. Meanwhile, biodiversity loss has a much longer history. ‘Records and information in recent literature rarely go back beyond the 1970s’, so that anecdotal information has to be painstakingly processed to estimate the actual extent of the biodiversity crisis (Schulze-Hagen 2019). Lack of knowledge and a widespread historical amnesia are considered to be the reason why society remains so strangely unfazed by the loss of biodiversity (Saenz-Arroyo et al. 2005). In continually changing systems such as cultural landscapes, the shifting baseline syndrome can lead to a continued deterioration of the baseline conditions (Clavero 2014, Pauly 1995) and thus to increasingly unambitious targets. The NRR also makes this mistake by using the status of 2025 as a baseline for common farmland birds, for example, and setting a blanket increase of 30 % by 2050. Godet et al. (2022) point out that there must be different baseline conditions depending on the object and that these must not be seen as immediate targets, but as a starting point for collective discussions of targets under current conditions – from a natural science as well as from a social science perspective (Godet et al. 2022). This requires an intensive debate to define the recovery targets in the national recovery plans (see also Action 5 below).

Action 4: Better consideration of the consequences of the climate crisis and other stressors for nature conservation

As things stand, changes caused by climate change only have to be taken into account for habitat types that lie outside Natura 2000 sites. Derogations of the NRR are possible on the basis of such changes. We believe it is essential that restoration plans consider preparing all ecosystems for the plausible future that climate change will bring, even if we cannot plan for this future in detail due to its irreducible uncertainty. If it is determined that restoration goals cannot be met due to changes in climatic factors, this must lead to modified restoration goals, not their abandonment.

In view of the rapidly progressing degradation of ecosystems and their elements, a constructive approach to the NRR is, from an ecological point of view, already a challenge. There is neither evidence nor any adequate feasibility study that the NRR, in its current, politically watered-down form, can make a sufficiently effective contribution to achieving its goals. The effectiveness and the demands of the NRR collide dramatically with current environmental dynamics. The affected ecosystems are often already so severely damaged that many changes are likely to be irreversible. The loss of genetic diversity and of the minimum areas required to maintain critically endangered populations and ecological processes appear to be disastrous in themselves.

In addition to the large number of stress situations occurring in ecosystems and the stressors that trigger them, there are cumulative and systemic feedback effects. If we fail to contain the anthropogenic climate crisis, very fundamental problems will arise (not only) in the restoration of ecosystems.

The current discourse on the NRR and on the need and potential for action appears to be almost entirely decoupled from the research fields and science outlined above. What is clear is that the current increase in uncertainty, even with regard to short-term climate developments, presents a significant dilemma. In this context, a guideline from the EU Commission would be helpful – for example, in the form of secondary or delegated legislation that could regulate the (urgently needed) adaptation of the Habitats Directive to climate crisis-induced effects and the necessary handling of irreducible uncertainty. This, of course, on condition that the objectives are not fundamentally weakened (on ecologically sustainable concepts of restoration for forest ecosystems, see also Bou Dagher Kharrat et al. 2023).

Action 5: Adapting nature conservation objectives and making them more dynamic

On the one hand, we are aware that a departure from standard assumptions about the condition of certain ecosystems (habitat types) poses a fundamental challenge for nature conservation in terms of justification and legitimization. On the other hand, however, we are convinced that there are good reasons for more nature conservation with modified sets of objectives. In any case, it would be negligent not to question these objectives for short-term tactical reasons when they no longer appear achievable despite the long-term implementation of very expensive measures. All prescriptive concepts that aim at too narrowly defined and discrete ecosystem conditions, and whose success depends solely on the presence of individual species, are no longer tenable in the context of the evidence of ecosystem change and the climate crisis. However, this does not mean that protected areas and the revitalization of ecosystems are becoming redundant. On the contrary, there is an ever-increasing need to strengthen the functionality and adaptability of ecosystems. This means that, within the framework of ecosystem-based approaches, the abiotic and biotic conditions required for this must be guaranteed to the best possible extent (Ibisch 2022).

Specifically, it is also important that the NRR should allow and promote wilderness concepts (e.g. succession, natural forest development without biomass use) and process-oriented developments in the sense of restoring ecosystem functions. Examples include the restoration of ancient forests or proforestation as a nature-based solution, i.e. the protection and maintenance of existing forests by maximizing their carbon storage and climate impact, the promotion of their biodiversity and natural processes (e.g. DellaSala et al. 2020, Moomaw et al. 2019), including extensive grazing practices, floodplain development with natural water dynamics and the promotion of light forests, as well as temporarily forest-free sites created by disturbances (e.g. Araújo et al. 2024, Fartmann et al. 2021, FAZ 2024, Luick et al. 2025 c).

Science and conservation practitioners are ready and willing to contribute their evidence-based knowledge to the implementation of the NRR, particularly with regard to managing the risks of climate change and developing more process-oriented conservation concepts.

Action 6: Establish an independent and well-equipped means of financing

The cross-references to numerous existing legal obligations and funding programs for agriculture and forestry (primarily the CAP) and in nature conservation have led to the opinion, particularly in political circles, that no separate financial resources are needed to implement the NRR and that only different allocations are required. Although the EU Commission intends to present proposals for financing in the coming months, it was already announced when the draft legislation was presented in 2022 that the funds for implementation could largely be drawn from existing EU coffers, for example from the existing biodiversity funding for the current financial period 2021–2027 totaling 100 billion €. European environmental organizations, on the other hand, are calling for a separate fund for the implementation of the NRR and an additional 15 to 25 billion € annually (BirdLife Europe et al. 2024). We strongly support this crucial demand. In their statement on renaturation, the advisory councils SRU, WBBGR and WBW (2024) also emphasize the need to convince land users by improving the legal and economic framework for renaturation, in particular by providing incentives for private projects and adequate remuneration for the provision of public goods.

Action 7: Counter the massive delays that can be expected in implementation with solution-oriented, forward-looking action

Not only in view of the – as yet unaddressed – political dissent regarding the NRR (cf. Luick et al. 2025 a) but also in view of the legislation’s shortcomings, it is to be feared that the early results of the new law will be political poker and bureaucratic red tape. Given this fear, it is important that solutions are found now, so that the implementation of the NFL can develop positively after all. The following developments, in particular, are foreseeable:

- Many EU member states will continue to express strong criticism and, in particular, demand an extension of the deadlines for the draft national recovery plans (NRP) on the grounds of the significant additional procedural and administrative burden. The fact that this delaying tactic has a good chance of success is demonstrated by the current debate on the regulation on deforestation-free supply chains (EUDR). This was supposed to come into force on 1 December 2024 and has been postponed by the new EU Commission, initially to 30 December 2025 and, for small companies, to 30 June 2026 (BMEL 2025, EC 2024 a, b).

- Based on recent experience with (non-)fact-based arguments (including the amendment of the Federal Forest Act, Deforestation Ordinance) from the various stakeholder groups in the field of agrarian and forestry associations and environmental NGOs, it seems almost impossible to develop constructive solutions based on mutual understanding of concerns.

- The quality of many of the submitted NRPs will presumably be very weak, inadequate to the point of being unacceptable, and, above all, they will not be submitted in a timely manner.

- The Member States will attempt creatively to declare existing activities in the land use sector (agriculture and forestry) as meeting WVO objectives. This can be seen, for example, in the response to a question from the Bundestag to the federal government, which suggests simply attempting to summarize or partially report on areas that are already protected, along with their associated management plans and relabeling these in order to achieve the NRR targets. Among the sites mentioned are Natura 2000 areas, nature reserves, forest reserves of various categories, national parks, biosphere reserves, landscape protection areas, nature parks and national natural monuments (CDU & CSU 2024). However, this would not even begin to achieve the goals of the legislation and would jeopardize the interim targets for 2030.

- The NRR demands the improvement and restoration of habitats suffering from deficits. At the same time, however, the wording contains no obligation to achieve a state of success. Failure to secure success does not violate the legislation, since it suffices if measures are merely initiated. Indeed, the member states are also allowed to establish strategies that are indefinite and not legally enforceable.

- The provision of dedicated financing for nature restoration will only be politically possible in the medium to long term, if at all.

The commitment to phase out biodiversity-damaging subsidies by 2020, as set out in the Aichi Targets of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD 2010, 2020), remains unfulfilled. But as a detailed report by Dasgupta shockingly shows, the opposite has actually occurred (Dasgupta 2021; compare Luick et al. 2025 a). At the 15th United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP 15) in December 2022, the elimination of environmentally harmful subsidies by 2030 was agreed again: incentives and subsidies with negative impacts on biodiversity are to be identified by 2025 and discontinued by 2030. Environmentally harmful subsidies are to be reduced by at least 500 billion US $ per year by 2030 (UNEP 2023, NEFO 2024).

In sum, the implementation challenges listed can be said to be ‘wicked problems’ (tricky, complex challenges). This concept, developed in the late 1960s, has been particularly influential in sustainability research and public administration (Pashkevich 2020). Wicked problems are characterized by a lack of clear definition, the possibility of conflicting values among stakeholders and the absence of clear-cut solutions (Poeck & Lönngren 2019). Nevertheless, there are reasonable options for overcoming all the foreseeable obstacles and conflicts. Identifying them today, working through them and – voluntarily if necessary – making qualitatively better decisions, which are also necessary decisions, is absolutely essential to achieving the goals. These should not be abandoned just because they appear difficult. The federal government should define ambitious measures for implementation in the national recovery plan, based on scientific research. Inter- and transdisciplinary scientific guidance is needed to develop and implement solutions to the wicked problems, because the successful implementation of the NRR means nothing less than a fundamental transformation of large parts of the cultural landscape.

Action 8: Testing exemplary implementation paths in landscape living labs in a research-led and co-creative manner

The multiple challenges described above for implementing the NRR require an intensive transdisciplinary, scientifically sound multi-stakeholder approach. The concept of ‘landscape living labs’, which comes from transdisciplinary and transformative sustainability research, aims to establish a scientific research and development infrastructure ‘in reality’ in the existing world, thus opening up spaces for experimentation in the midst of society. New ideas, inventions and solutions are developed, tested, researched and further developed in a participatory manner under real-life conditions (Parodi et al. 2024).

This concept already plays a central role in the EU mission ‘A Soil Deal for Europe’, which aims to restore 75% of soils in the EU to health by 2030 (EC 2024 c). With the aim of transforming agricultural and food systems, the Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) is working with three Hessian universities to establish five real-world laboratories (Gunnoltz et al. 2024). Real-world laboratories with co-creative working methods have also been proposed for the development of biodiversity-oriented model landscapes in Baden-Württemberg (Jedicke et al. 2023). According to Parodi et al. (2024), the core characteristics of such real-world laboratories are research orientation, transformative potential, normativity and sustainability, transdisciplinarity and participation, civil society orientation, exemplarity and transferability, long-term orientation, experimentality and education/learning.

Due to the manifold challenges in the form of wicked problems, the necessary scientific research and support, and the requisite co-creative development, evaluation and follow-up processes, we propose developing, implementing, monitoring and iteratively adapting the necessary steps for effective implementation of the NRR in representative rural areas in all German federal states. This would also create valuable educational and learning opportunities, as well as models for cooperation, which would provide crucial support for the implementation of the synergistic legal norms described in Section 4. If a real-world laboratory were to be set up in each of the federal states, they would require an annual budget of approximately 30 to 40 million € – a good investment of seed funding.

6 Outlook

From a scientific point of view, there is no question that the NRR, as adopted, is an important and necessary instrument for achieving the EU’s own targets for environmental and nature conservation in the Green Deal project. Restoration measures are urgently needed to promote the resilience and adaptive capacity of ecosystems and to create synergies with climate change mitigation and adaptation (see SRU, WBBGR & WBW 2024). This must be clearly communicated again and again during the implementation process in order to strengthen acceptance and willingness to participate. The same applies to the major economic benefits of nature restoration: the European Commission estimates that restoring 90% of degraded ecosystems by 2050 would create an economic value of €1.86 trillion, twelve times the expected restoration costs (see SRU, WBBGR & WBW 2024).

With all the qualifications and problems mentioned (see also Luick et al. 2025 a), it is clear that the NRR is the most realistic compromise possible in the present political polycrisis, but it does at least advance the debate and define concrete measures that need to be taken, as well as suggesting possible ways forward.

With the NRR the overarching goal of restoring destroyed and impaired ecosystems has now been enshrined in law and is legally enforceable for the first time. The member states have an obligation and must in future not only draw up restoration plans with specific targets and implementation methods, but the implementation process must be designed with a strict timetable and in a publicly transparent manner, with the mandatory use of appropriate monitoring procedures and instruments. This is a clear innovation and a much better basis for future political discourse on ecological sustainability issues than has existed so far on the basis of other legal instruments, such as the Habitats Directive.

The decisive factor will be the seriousness with which the EU member states now implement the NRR, both legislatively and practically. However, it is not at the discretion of the member states whether ‘necessary’ measures are taken; the NRR obliges them to do so. That said, the term ‘necessary’ is open to interpretation. Article 14 of the NRR can also be interpreted to mean that the member states must first implement preparatory monitoring systems and undertake research to determine the nature of (and need for) targeted recovery measures. Our concern is that such a legal interpretation could delay the effectiveness of the NRR for a very long time. Time is pressing and it would be irresponsible to block the changes that are needed with such tricks. After all, nothing less than the realization of a survival ecology for humankind is at stake.

- The NRR is an important instrument for achieving climate protection goals. The extent to which EU member states implement the NRR in legislation and practice will depend on the seriousness and positive, enabling and non-obstructive attitude with which they do so.

- The acceleration of climate change means that even in the short term, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the achievability of static restoration targets. At the same time, however, it increases the need for action with regard to functional and ecosystem-based approaches to landscape revitalization.

- At the national and federal level, extensive adjustments are needed in specialized laws and secondary legislative instruments, which means a high risk of delays in implementation. However, these offer the opportunity to achieve significant synergies between different policy objectives.

- Sector coupling and the synergies that this creates with other projects must be implemented as a matter of urgency. These include, among others, the Natural Climate Protection Action Program, the National Strategy on Biological Diversity 2030 and the Forest Strategy 2050.

- Additional, sufficient and long-term financial resources must be provided at the EU, national and federal levels. The objectives of the NRR cannot be realized with the currently available departmental funds (such as GAP, LIFE, GAK, ANK) alone. In addition, more flexible funding and support instruments that can be adapted to the specific conditions of the regions, ownership and development goals are urgently needed, especially for the restoration of forest ecosystems. The establishment of real-world laboratories for co-creative, model implementation, closely monitored by the scientific community, would be an efficient and effective way to improve implementation and the continuous acquisition of knowledge.

- New legislation (regulatory law), political goals of any degree of ambition or even funding guidelines with ample financial resources alone will not guarantee the implementation of the NRR, but at best promote it. The actual measures must be implemented in specific locations. It is therefore important to motivate landowners at all levels and to create economic opportunities through attractive ‘participation offers’. In the majority of ecologically deficient areas, it will not be possible to achieve the area targets through action on state-owned property alone; in open land in particular, cooperation and alliances are needed with private landowners and land users.

Araújo, M.B., Alagador, D. (2024): Expanding European protected areas through Rewilding. Current Biology 34, 1–10. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.07.045. Bai, Y., Cotrufo, M.F. (2022): Grassland soil carbon sequestration: Current understanding, challenges, and Solutions. Science 377, 603-608. DOI: 10.1126/science.abo2380.

BirdLife Europe, WWF Europe, EEB (European Environmental Bureau), Euronatur & CEE Bankwatch Network (2024): Call for a dedicated EU Nature Restoration Fund. https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/call-for-a-dedicated-eu-nature-restoration-fund-_july-2024.pdf.

BfN (Bundesamt für Naturschutz) (2024): EU Nature Restoration Law: Faktencheck zur Verordnung zur Wiederherstellung der Natur. https://www.bfn.de/aktuelles/eu-nature-restoration-law-faktencheck-zur-verordnung-zur-wiederherstellung-der-natur.

BfN (Bundesamt für Naturschutz) (2025): Indikator Artenvielfalt und Landschaftsqualität. https://www.bfn.de/indikator-artenvielfalt-und-landschaftsqualitaet

BMEL (Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft) (2024): Der Wald in Deutschland – ausgewählte Ergebnisse der vierten Bundeswaldinventur. https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Broschueren/vierte-bundeswaldinventur.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5.

BMEL (Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (2025): EU-weit einheitliche Regelung für entwaldungsfreie Lieferketten. https://www.bmel.de/DE/themen/wald/waelder-weltweit/entwaldungsfreie-Lieferketten-eu-vo.html.

BMUV (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz) (2020): Die Lage der Natur in Deutschland – Ergebnisse von EU-Vogelschutz- und FFH-Bericht. https://www.bfn.de/sites/default/files/BfN/natura2000/Dokumente/bericht_lage_natur_2020.pdf.

BMUV (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz) (2024a): Die Nationale Strategie zur Biologischen Vielfalt 2030 (NBS 2030). https://www.bmuv.de/download/die-nationale-strategie-zur-biologischen-vielfalt-2030-nbs-2030

BMUV (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz) (2024b): Natura 2000. https://www.bmuv.de/themen/naturschutz/gebietsschutz-und-vernetzung/natura-2000/schutzgebietsnetz-natura-2000.

BMUV (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz) (2025): Prioritärer Aktionsrahmen (PAF) für Natura 2000 in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland gemäß Artikel 8 der Richtlinie 92/43/EWG des Rates zur Erhaltung der natürlichen Lebensräume sowie der wildlebenden Tiere und Pflanzen (Habitat-Richtlinie) für den Zeitraum 2021-2027. https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Naturschutz/natura_2000_prioritaerer_aktionsrahmen_bf.pdf.

BMUV (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz) & BfN (Bundesamt für Naturschutz (2021): Auenzustandsbericht 2021 – Flussauen. 72 S. https://www.bfn.de/sites/default/files/2021-04/AZB_2021_bf.pdf.

Bou Dagher Kharrat, M., Pötzelsberger, E., Nabuurs, J., Bauhus, J., O’Hara, J., Alberdi, I., Horstmann, N., Hunziker, M., Lundhede, T., Schifferdecker, G., Lovric, N., Khalabuzar, K., Svensson, J. (2023): SUPERB’s Policy recommendations for the EU Nature restoration Law Towards biodiverse and adaptive forest landscapes for Europe’s people. https://forest-restoration.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Nature-Restoration-Law_PolicyBrief.pdf.

Brlík, V., Šilarová, E., Škorpilová, J., Klvanova, A. + 64 authors (2021): Long-term and large-scale multispecies dataset tracking population changes of common European breeding birds. Scientific Data 8(1):21. DOI: 10.1038/s41597-021-00804-2.

CBD (Convention on Biodiversity) (2010, 2020): Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, including Aichi Biodiversity Targets. https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets.

CDU & CSU (2024): Kleine Anfrage der Fraktion der CDU/CSU, Umsetzung EU-Verordnung zur Wiederherstellung der Natur. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/129/2012986.pdf.

CEU (Council of the European Union) (2024): What is the state of nature in the EU? https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/state-of-eu-nature/.

Clavero, M. (2014): Sifting baselines and the conservation of non-native species. Conserv. Biol. 28 (5), 1434-1436. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12266

Dasgupta, P. (2021): The Economics of Biodiversity – The Dasgupta Review. Full Report. 610 p. (London: HM Treasury). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review.

DellaSala, D.A., Kormos, C.F., Keith, H., Mackey, B., Young, V., Rogers, B., Mittermeier, R.A. (2020): Primary forests are undervalued in the climate emergency. BioScience 70 (6), 445-445. DOI: org/10.1093/biosci/biaa030.

EC (European Commission) (2020): EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 – Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380.

EC (European Commission) (2022a): Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration – COM/2022/304 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0304.

EC (European Commission) (2022b): Commission staff working document – Impact Assessment – Accompanying the proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration, COM (2022) 304 final, SEC(2022) 256 final, SWD(2022) 168 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022SC0167&qid=1686750707844.

EC (European Commission) (2022c): Commission staff working document - criteria and guidance for protected areas designations. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/document/download/12d0d249-0cdc-4af9-bc91-37e011620024_en?filename=SWD_guidance_protected_areas.pdf.

EC (European Commission) (2024a): Commission strengthens support for EU Deforestation Regulation implementation and proposes extra 12 months of phasing-in time, responding to calls by global partners. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_5009.

EC (European Commission) (2024b): Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 as regards provisions relating to the date of application. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52024PC0452R(01).

EC (European Commission) (2024c): EU Mission: A Soil Deal for Europe. op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7d4bea74-a238-11ef-85f0-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

EU (European Union) (2022): Richtlinie (EU) 2022/2464 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 14. Dezember 2022 zur Änderung der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 537/2014 und der Richtlinien 2004/109/EG, 2006/43/EG und 2013/34/EU hinsichtlich der Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung von Unternehmen. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022L2464.

EU (European Union) (2024): Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on nature restoration and amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869 (Text with EEA relevance). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1991&qid=1722240349976.

ECA (European Court of Auditors) (2024): Common Agricultural Policy Plans – Greener, but not matching the EU’s ambitions for the climate and the environment. Special Report, 56 p. https://www.eca.europa.eu/ECAPublications/SR-2024-20/SR-2024-20_EN.pdf.

Fartmann, T., Jedicke, E., Streitberger, M., Stuhldreher, G. (2021): Insektensterben in Mitteleuropa. Ursachen und Gegenmaßnahmen. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart.

FAZ (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) (2024): Ein Viertel Europas könnte wieder Wildnis werden. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wissen/erde-klima/wilde-natur-in-europa-ein-viertel-des-kontinents-koennte-wieder-wildnis-werden-19928375.html.

Forest Europe (2020): State of Europe’s Forests 2020. https://foresteurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/SoEF_2020.pdf.

Friedrichs, M., Hermoso, V., Bremerich, V., Langhans, S.D. (2018): Evaluation of habitat protection under the European Natura 2000 conservation network – the example for Germany. PLoS ONE 13 (12): e0208264. DOI: org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208264.

Gardner, C., Bullock, J. (2021): In the climate emergency, conservation must become survival ecology. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2, 659912. DOI: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.659912.

Godet, L., Dufour, S., Rollet, A.-J. (eds., 2022): The Baseline Concept: A Narrow Path Between False Trails and True Impasses. In: The Baseline Concept in Biodiversity Conservation (eds L. Godet, S. Dufour and A.-J. Rollet). DOI: org/10.1002/9781394173679.

Gunnoltz, J., Jacob, K., Brüser, K., Breuer, L., Matzdorf, B., Ewert, F. (2024): Reallabore in Agrarlandschaften: Ausgestaltung und Handlungsempfehlungen. ZALF-Policy Paper 11/24, Müncheberg, 9 S. https://www.zalf.de/de/forschung_lehre/publikationen/Documents/Policy_Paper/ZAF_Policy-Paper-Reallabore.pdf.

Ibisch, P.L. (2022): Ein ökosystembasierter Ansatz für den Umgang mit der Waldkrise in der Klimakrise. Natur und Landschaft 97 (7), 325-333. DOI: .org/10.19217/NuL2022-07-02.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023): Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 184 pp. DOI: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

Jedicke, E., Mayer, M., Bürckmann, H., Trautner, J., Sliva, J. (2023): Konzept für kooperativ entwickelte biodiversitätsorientierte Modelllandschaften in Baden-Württemberg. – Ministerium für Umwelt, Klima und Energiewirtschaft Baden-Württemberg, Ministerium für Ernährung, Ländlichen Raum und Verbraucherschutz Baden-Württemberg, Ministerium für Verkehr Baden-Württemberg (Hrsg.), Stuttgart, 64 S.

Jones, A., Fernandez Ugalde, O., Scarpa, S., Eiselt, B. (2022): LUCAS Soil 2022 – JRC Technical Report. JRC Publications Repository, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. DOI: 10.2760/74624.

Kreibich, N., Kühlert, M., Brod, S. (2024): Unternehmen in der Transformationsverantwortung: Das Contribution-Claim-Modell als Alternative zur CO2-Kompensation. GAIA 33/2, 263–264. DOI: 10.14512/gaia.33.2.25.

Luick, R., Hennenberg, K., Leuschner, C., Grossmann, M., Jedicke, E., Schoof, N., Waldenspuhl, T. (2022): Urwälder, Natur- und Wirtschaftswälder im Kontext von Biodiversitäts- und Klimaschutz. Teil 2: Das Narrativ von der Klimaneutralität der Ressource Holz. Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung 54 (1): 22-35. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1399/NuL.2022.01.02. Zugleich als englische Fassung: Primeval, natural and commercial forests in the context of biodiversity and climate protection. Part 2: The narrative of the climate neutrality of wood as a resource. DOI: org/10.1399/NuL.2022.01.02.e.

Luick, R., Jedicke, E., Fartmann, T., Grossmann, M., Potthast, T. (2025a): Die EU-Verordnung über die Wiederherstellung der Natur. Hintergrund, Entstehung und Verlauf des Gesetzgebungsverfahrens – ein Rückblick. Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung 57 (3), 12-21. DOI: 10.1399/NuL.108632.

Luick, R., Jedicke, E., Fartmann, T., Grossmann, M., Potthast, T., Ibisch, P. (2025b): Unsere Wälder im Spannungsfeld von Klimaschutz und Ressourcenbereitstellung – Bilanzierung und Prognosen der LULUCF-Ziele und Konsequenzen für das politische, planerische und praktische Handeln. Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung 57 (5), eingereicht.

Luick, R., Freese, J., Jedicke, E., Weber, G., Reisinger, E. (2025c): Extensive Weidesysteme als Strategie für den Naturschutz. In: Brackane, S., Hackländer, K., Hrsg., Die Rückkehr der großen Pflanzenfresser – Konfliktfeld oder Chance für den Artenschutz? Oekom, München, 311-341. DOI: org/10.14512/9783987262562.

MLEUV (Ministerium für Land- und Ernährungswirtschaft, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, 2025): Brandenburg setzt Vollzug der EU-Wiederherstellungsverordnung vorläufig aus. https://mleuv.brandenburg.de/mleuv/de/aktuelles/presseinformationen/detail/~26-02-2025-brandenburg-setzt-eu-wiederherstellungsverordnung-aus#.

Moomaw, W.R., Masino, S.A., Faison, E.K. (2019): Intact forests in the United States: Proforestation mitigates climate change and serves the greatest good. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 2, 449206. DOI: org/10.3389/ffgc.2019.00027.

NEFO (Netzwerk-Forum zur Biodiversitätsforschung Deutschland) (2024): Post-2020 CBD Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) – Ergebnis der CBD COP-15: 23 neue globale Biodiversitätsziele bis 2030. https://www.ufz.de/nefo/index.php?de=47996.

Parodi, O., Ober, S., Lang, D.J., Albiez, M. (2024): Reallabor versus Realexperiment: Was macht den Unterschied? GAIA 33 (2), 216-221. DOI: org/10.14512/gaia.33.2.4.

Pashkevich, N. (2020): Wicked Problems: Background and Current State. Philosophia Reformata 85 (2), 119-124. DOI: org/10.1163/23528230-8502A008. Pauly, D. (1995): Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trend in Ecology and Evolution 10, 430. DOI: org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)89171-5.

Poeck, K. van, Lönngren, J. (2019): Wicked problems: a systematic review of the literature. ECER 2019, European Conference on Educational Research, Education in an era of risk: the role of educational research for the future, Abstracts. https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/8635228.

Saenz-Arroyo, A., Roberts, C.M., Torre, J., Carno-Olvera, M., Enriquez-Andrade, R.R. (2005): Rapidly shifting environmental baselines among fisher of the Gulf of California. Proc. Roy. Soc. B 272, 1957-1962. DOI: org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3175

Schulze-Hagen, K. (2019): Das shifting-baseline-Syndrom und die „Wilden Weiden”. In: Bunzel-Drüke, M., Reisinger, E., Böhm, C., Buse + 34 authors, Naturnahe Beweidung und NATURA 2000 – Ganzjahresbeweidung im Management von Lebensraumtypen und Arten im europäischen Schutzgebietssystem NATURA 2000, 2. Aufl., ABU Biologische Station, Hrsg., Bad Sassendorf-Lohne, 36-41.

SRU, WBBGR, WBW (Sachverständigenrat für Umweltfragen; Wissenschaftlicher Beirat für Biodiversität und Genetische Ressourcen; Wissenschaftlicher Beirat für Waldpolitik) (2024): Renaturierung: Biodiversität stärken, Flächen zukunftsfähig bewirtschaften. Stellungnahme, aktualisierte Fassung August 2024. Berlin, 88 S and short version in English. https://www.umweltrat.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/04_Stellungnahmen/2020_2024/2024_08_Aktualisierung_Renaturierung.html. https://www.umweltrat.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/04_Statements/2020_2024/2024_06_Statement_Nature_restoration.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=11.

Tomppo, E., Gschwantner, T., Lawrence, M., McRoberts, R. (2010): National Forest Inventories Pathways for Common Reporting. Springer, 638 p. DOI: 10.1007/978-90-481-3233-1.

UBA (Umweltbundesamt, 2022a): Die Wasserrahmenrichtlinie – Gewässer in Deutschland 2021, Fortschritte und Herausforderungen. Dessau, 124 S. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/die-wasserrahmenrichtlinie-gewaesser-in-deutschland.

UBA (Umweltbundesamt, 2022b): Gewässer in Deutschland – Dashboard des Bundes zur Umsetzung der Wasserrahmenrichtlinie. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/301dacb12edd4501a6a97874da0738d0/.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2023): Report of the conference of the parties (COP) of the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity on the second part of its 15th meeting (Globale Biodiversitätsrahmen von Kumming-Montreal / GBF, Global Biodiversity Framework). https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/f98d/390c/d25842dd39bd8dc3d7d2ae14/cop-15-17-en.pdf.

Vogt, P., Riitters, K., Caudullo, G., Eckhard, B. (2019): FAO – State of the World’s Forests: Forest Fragmentation. JRC Publications Repository, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. DOI:10.2760/145325.

This article analyses the upcoming implementation of the Nature Restoration Law (NRL) based on current knowledge, from the perspective of ecological sciences. The EU regulation on nature restoration came into force in 2024. The official German legal term for the EU law is Wiederherstellungsverordnung (WVO). Central aspects are presented and the given roadmap for implementation is described, starting with National Restoration Plans (NRP), which Member States must submit in draft form to the Commission by 1st September 2026, following a mandatory participation process. Cross-references to other legal obligations at a global, EU, and national level are also analysed. These result in opportunities for a wide range of synergies, provided that appropriate sector coupling is implemented legislatively and practically through legal adjustments. It also becomes clear that effective implementation depends equally, among others, on: (1) an overall ambitious framework in the NRP; (2) a consistent move away from environmentally harmful subsidies; (3) the provision of specific financial resources in sufficient quantities, and (4) on the motivation of landowners and land users to participate in implementation through economic incentives.

Die Umsetzung der EU-Wiederherstellungsverordnung

Inhaltliche Details, Fahrplan und kritische Reflexion

Der Beitrag analysiert nach aktuellem Kenntnisstand die anstehende Umsetzung des Nature Restoration Law (NRL), der 2024 in Kraft getretenen EU-Verordnung 2024/1991 über die Wiederherstellung der Natur (WVO), aus Perspektive der ökologischen Wissenschaften. Wichtige Inhalte und terminierte Zielsetzungen werden vorgestellt, beginnend mit den nationalen Wiederherstellungsplänen (NWP), welche die Mitgliedstaaten nach einem verpflichteten Beteiligungsprozess bis zum 1.9.2026 der Kommission im Entwurf vorzulegen haben. Es werden Querbezüge zu anderen Rechtsverpflichtungen auf globaler, EU- und nationaler Ebene analysiert. Aus diesen resultieren Chancen für vielfältige Synergien, sofern mögliche und sinnvolle Sektorkopplungen durch rechtliche Anpassungen legislativ und praktisch vollzogen werden. Deutlich wird, dass eine wirksame Umsetzung essenziell von verschiedenen Faktoren abhängig ist, unter anderem von (1) einer insgesamt ambitionierten Rahmengebung im NWP; (2) einer konsequenten Abkehr von umweltschädlichen Subventionen; (3) der Bereitstellung spezifischer Finanzmittel in ausreichendem Umfang und (4) der Motivation von Flächenbesitzenden und Landnutzenden zur Umsetzungsbeteiligung durch wirtschaftliche Anreize.

Zu diesem Artikel liegen noch keine Kommentare vor.

Artikel kommentierenSchreiben Sie den ersten Kommentar.