The EU Nature Restoration Law

On 18th August 2024, the EU Nature Restoration Law (NRL) came into force. The NRL is an important part of the European Commission’s Green Deal project and serves to implement legally binding UN agreements for the protection of nature and the climate (such as the Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity). The draft text changed substantially in the highly controversial legislative process from its introduction to its adoption and threatened to fail on several occasions. This article describes the legislative process and the background to it from the perspective of conservation researchers. It is important to be aware of this process and background in order to understand and support the restoration plans to be submitted by the member states by 1st September 2026, which include specific targets and implementation pathways. The creation and adoption of the NRL can be attributed to a unique political window of opportunity. Submitted on 18.12.2024, accepted on 20.01.2025.

von Rainer Luick, Eckhard Jedicke, Thomas Fartmann, Manfred Großmann and Thomas Potthast erschienen am 28.02.2025 DOI: 10.1399/NuL.110576Dieser Beitrag ist auch in deutscher Sprache verfügbar: www.nul-online.de, DOI:10.1399/NuL.108632.

1 Introduction and Background

On 18th August 2024, the EU Nature Restoration Law (NRL) came into force (EU 2024), also known in German as Renaturierungsgesetz or officially as Wiederherstellungsverordnung (WVO). In this paper and two follow-up articles, we present the political and legal architecture in which the NRL is embedded, and which at first glance may not appear entirely self-evident. We also show interrelations with (and impacts on) other policy areas. This requires an overview of the complex mix of international, European and national strategies and legal norms in play.

To understand the content of the NRL, it is necessary to look at the original impetus, the intentions and aims of the proposal developed by the European Commission, and at the course of the legislative process in the two legislative bodies of the EU, the Parliament and the Council. We also present arguments justifying the need for the NRL to have the force of binding law for all EU member states, and we offer analyses of possible implications and problems of implementation. For example, in a follow-up article (Luick et al. 2025 a; submitted), the topic of forests is considered from a forest-ecological and an environmental policy perspective, two perspectives that do not automatically harmonise. The forestry sector has already experienced the most significant concretisations in the NRL. For this sector, therefore, mechanisms are developed that can also be used to restore other ecosystems.

What is the content of the NRL? The core objective is not only to maintain the ecological performance of ecosystems in their current state, but also to restore ecosystems that have already been destroyed or damaged. The NRL is the first law worldwide in which an entire community of states recognises that nature is essential for human survival and is committed to the associated remedial tasks. The NRL aims to integrate these goals into an effective overall strategy, in particular concerning climate protection and land use (see Luick et al. 2025 a; submitted).

The EU Commission launched the legislative initiative for the NRL on 22nd June 2022 after difficult preparatory work (EC 2022 a). The two years leading up to its adoption in June 2024 were characterised by intense, often heated debates, and more than once the legislative process threatened to fail.

The political dimension of the NRL is multi-layered. First of all, the NRL is a key measure for the legislative implementation of the ecological goals of the European Union’s Green Deal strategy, which also includes the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 and the EU Forest Strategy 2030. At the same time, however, the NRL can also be seen as an important instrument for implementing the legally binding obligations under international law arising from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological Diversity, which have been ratified by the EU and all its member states (UNEP 1992, 2011, 2023).

The draft of the NRL was published on 22nd June 2022, at the same time as the draft of the Sustainable Use Regulation (SUR), which also derives from the Green Deal. The discussion of both laws in the European Council and Parliament was seen as a package. The SUR is meant to lead to a 50% reduction in the use of pesticides (plant protection products, PPPs) in agriculture by 2030 – these have been shown to endanger the environment and human health – as well as a ban on PPPs in ‘sensitive areas’ (protected areas under the EU Water Framework Directive and Natura 2000 sites). The draft SUR presented by the Commission received strong support from institutions and NGOs in the environmental, health and consumer protection sectors. At the same time, however, fierce resistance emerged from agricultural and other commercial land users. The draft of the SUR failed at its first parliamentary hurdle on 22nd November 2023 due to the effects of massive lobbying by these groups. This put an end to the legislative process and the ‘nature conservation package’ of the NRL and SUR, which was planned as part of the Green Deal, was abandoned.

2 The starting point for the NRL – the state of nature

2.1 The global situation

Planetary boundaries (also been referred to as Earth-system boundaries) currently define ecological limits for nine biophysical systems and processes that regulate the functioning of life-supporting systems on Earth and thus also determine the stability and resilience of the Earth system (Rockström et al. 2009, 2023, PIK 2024, Fig. 1). Exceeding the defined boundaries endangers the stability of the Earth system and thus the existence of human civilisation.

New assessments show that six of the nine planetary boundaries have now been exceeded, dramatically increasing the risk of large-scale, abrupt and irreversible environmental changes (tipping points) (e.g. Persson et al. 2022, Richardson et al. 2023, Fig. 1). Three of these planetary boundaries have already been exceeded to such an extent that a high-risk scenario has been reached: climate change, changes in biogeochemical cycles and changes in the integrity of the biosphere.

The latter complex includes planetary biological diversity and the stabilisation of the Earth system through essential ecological processes. Here, the boundaries have been irreversibly crossed: 75% of the land surface and 66% of the ocean area have been changed, in some cases drastically and irreversibly, by human influence, and over 85% of global wetlands have been completely lost in the last 100 years. Another indication is that, according to models and also on the basis of regional empirical studies, the extinction rate of organisms since the 1950s has increased by a factor of 100–1,000 compared to the natural extinction and emergence rate of new species (the reference is the averages of the last 10 million years of the Earth’s history). The rates in the coming decades will likely be 10,000 times higher (see, for example, De Vos et al. 2024, IPBES 2019, SCBD 2020). According to the ‘Living Planet Report 2024’ (WWF 2024), which regularly examines 5,500 vertebrate species in 35,000 populations worldwide, populations across all groups have declined by 73% over the past 50 years. Freshwater ecosystems (down 85 per cent), terrestrial ecosystems (down 69 per cent) and marine ecosystems (down 56 per cent) have been particularly affected. The NEXUS report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES 2024) estimates that every decade over the last 30–50 years, global biodiversity has declined by 2–6 per cent.

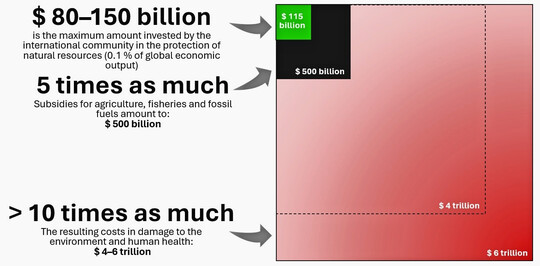

The Dasgupta Report (The Economy of Biodiversity, Dasgupta 2021), named after the British economist Sir Partha Dasgupta, highlights the economic and financial impacts of species extinction and environmental degradation, as well as the need to introduce natural capital into economic accounting systems. According to the report’s calculations, governments around the world spend approximately $500 billion annually on subsidies to the agriculture, fisheries and fossil fuels sectors. These subsidies cause environmental and health damage amounting to at least 4–6 trillion US dollars annually, while only a fraction of this is spent on protecting the natural environment: a maximum of 80–150 billion US dollars per year, which corresponds to a mere 0.1% of global economic output. Fig. 2 gives an idea of the proportions involved.

2.2 The situation in Europe and Germany

Assessments by the European Environment Agency (EEA) in the context of the effects of political and practical measures of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2020 (EC 2011) also paint an alarming picture of the state of nature. The focus is not on the ‘normal landscape’, where conditions are probably even more dramatic, but on the status of habitats and species in Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protection Areas (SPAs) under the EU Habitats and EU Bird Directive (EEA 2019, 2020, 2023, CEU 2024). Of the habitat types (in total across all groups and without taking into account the area proportions), 82% are in an ‘unfavourable’ to ‘inadequate’ state of conservation or in an ‘unfavourable’ to ‘poor’ state of conservation. This means that only 18% of the habitat types have the conservation status ‘favourable’. Due to a lack of data, it is not possible to present the area percentages in a pan-European context. But the following detailed picture emerges for extensive groups of habitat types that have been assessed as being in an adequate condition:

- Forests: 12 % (4 of 22 SACs),

- Grasslands: 8 % (2 of 25 SACs),

- upland and lowland moors: 0 % (0 of 16 SACs),

- freshwater habitats: 0 % (0 of 17 SACs).

There are 93 habitat types in Germany; of these, approximately 70% are predominantly open land habitat types, in an unfavourable conservation status The German government’s 2023 indicator report on the National Strategy for Biological Diversity firmly states that the current indicator value for the conservation status of habitat types and species listed in the Habitats Directive is not only far from the target range, but is also steadily deteriorating (Deutsche Bundesregierung 2021, 2023).

According to the targets of the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2020, at least 10% of the land should be placed under protection by 2023. According to an analysis of the designation of strictly protected areas with effective strategies, Germany, with currently only 0.6%, lags far behind in a European comparison (Gatti et al. 2023). The results of the 2007 National Biodiversity Strategy (NBS) are also disappointing, despite numerous campaigns and complex funding programmes; this is supported by evidence from various monitoring projects (including BMUV 2024 a, Deutsche Bundesregierung 2021, 2023, Hallmann et al. 2017, HBS & BUND 2025, Wirth et al 2015, 2024):

- According to the Red Lists of animals, plants and fungi, about 25% of the approximately 40,000 assessed species and subspecies in Germany are endangered, already extinct or missing; among the insect species, 34% of the 14,000 assessed species are endangered, already extinct or missing.

- About 31 % of plants, 20 % of fungi and lichens, 35 % of vertebrates and 32 % of invertebrates are endangered, already extinct or missing.

- There is extreme species loss in agricultural landscapes: of the bird species in open landscapes, 70% are considered endangered (many have already died out over large areas) and a further 13% are on the early warning list:

- The total biomass of flying insects has declined by around 70% since the 1980s.

- Since the 1990s, the population of wild bees has declined by approximately 42 %.

- Almost 70 % of biotope types (in terms of number) are in an inadequate or poor condition, especially agriculturally utilised grassland, but also inland waters and moors.

- According to the mandatory EU reporting for SPA and SAC protection areas, around 60% of the areas are in an inadequate or poor condition.

- Only 9% of surface waters are in a good condition.

- The HNV index (High Nature Value Farmland, agricultural land with high diversity) regularly assesses the state of the agrarian ‘normal landscapes’ in a representative manner using data from more than 1,700 sample areas. According to this, for the status year 2022, on average only about 13% of agricultural land provided significant positive ecological services: only 2.8% of agricultural land had an extremely high nature value. The NBS 2007 target for 2020 was 20%.

The NBS 2030 (BMUV 2024) responds to this by formulating clear targets for 2030, some of which are supplemented by targets for 2050. Target-specific indicators are intended to enable constant measurement and monitoring of the implementation status. The associated first action plan lists 21 fields of action for the years 2024–2027.

3 The framework of the NRL: the Green Deal, the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 and the EU Forest Strategy 2030

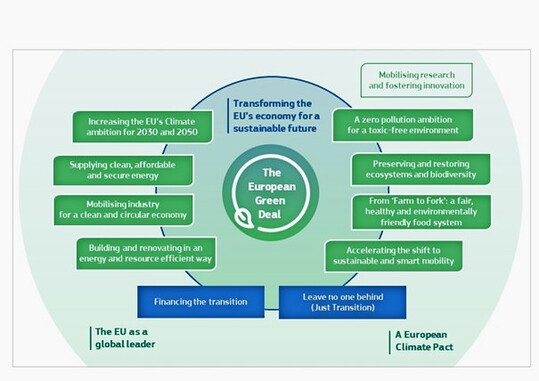

The European Green Deal is a policy programme presented by the first von der Leyen Commission on 11th December 2019 with the following objectives:

- reducing EU greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050, making it the first continent to become climate neutral; a special sub-package (‘Fit for 55’) has been created for this purpose, with the aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55% as early as 2030;

- preserving and enhancing Europe’s natural capital;

- generally steering the economy towards a sustainable transformation path.

The strategy is to be implemented by means of numerous individual legislative measures (EC 2019, 2021 a, Fig. 3). These include, in particular, the following, which are relevant to our paper and supplement the NRL:

- a new EU Climate Law;

- the revision of existing regulations and directives, including the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED), the EU Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry Regulation (LULUCF);

- the failed Sustainable Use Regulation (SUR) for more sustainable agriculture;

- the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), the implementation of which has been postponed until 2026;

- a reorientation of the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

The preamble to the Green Deal states that ‘all EU policies should contribute to maintaining and restoring Europe’s natural capital’. The section ‘Maintaining and Developing Ecosystems and Biodiversity’ announces concrete measures as part of a new biodiversity strategy for 2030 (EC 2020, submitted in 2021) and a forest strategy (EC 2021 b, submitted in 2021) that will build on it. The key demands and justifications from these two strategies that relate to forests are as follows:

- The existing network of protected areas should be extended to at least 30% of the land area. 10% of the land area should be strictly protected and forest ecosystems must make a significant contribution to this goal. Effective management rules should ensure protection.

- All remaining primary and old-growth forests (natural forests) should be mapped, strictly protected and monitored. Although they now account for only about 3% of the EU’s forest cover, they store significant amounts of carbon and continue to absorb additional carbon from the atmosphere. At the same time, they are essential for biodiversity and the provision of critical ecosystem services. It is also crucial to leave the dynamics of these forests to natural processes as far as possible, while finding synergies with sustainable ecotourism and recreation.

- The potential of sustainable afforestation should be harnessed to increase forest and tree cover. At least three billion additional trees should be planted by 2030, half of them in urban areas, while ‘fully respecting ecological principles’.

- Forestry practices that reduce biodiversity and cause a loss of carbon stored in roots and soil should be avoided.

- Climate change and the loss of biodiversity (including in forests) urgently require the ‘adaptive’ restoration of forests as part of ecosystem-based management approaches. In general, forest biodiversity must be better protected and restored to improve the resilience and adaptive capacity of forests.

In the political guidelines for her second Commission, von der Leyen announced that she would remain on track with the Green Deal in 2024 but would also launch numerous activities to strengthen the competitiveness of European industry and reduce energy prices. It remains to be seen how these potentially conflicting goals will actually be implemented and how much of the Green Deal’s just and necessary ambitions will be realised. Some important building blocks of the Green Deal, such as the SUR, were rejected, abandoned or only implemented in a watered-down form by the first von der Leyen Commission. It is already becoming apparent that the EU will not achieve its goal of becoming climate-neutral by 2050 with the measures currently in place, as the first interim targets are not even close to being met.

The NRL draft of the commission was accompanied by an extensive impact assessment of its possible ecological and socio-economic effects, including a detailed presentation of variants and options for action (EC 2022 b). The ‘Better Regulation Guidelines’ oblige the EU Commission to carry out such an ex-ante assessment of the impact of legislation, on a participatory and consultative basis, in order to both justify the necessary legal compliance and prevent unnecessary new bureaucracy (EC 2021, 2023). This well-founded, evidence-based assessment was, however, repeatedly called into question in the legislative process and also fundamentally ignored by some parliamentary circles. Sadly, this is not an isolated case, but rather ‘standard behaviour’ in national, European and global political negotiation processes for proposed legislation involving politically diverse and also lobby-oriented interests.

4 The process of creating the Restoration Law

The scientific basis for the NRL (and also the failed SUR) is the predominantly unfavourable ecological state of our natural and semi-natural ecosystems (see, e.g., De Vos et al. 2024, IPBES 2019, SCBD 2020, UN 2019, 2020, Wirth et al. 2024 and Section 2 above). As shown, this applies both in a global perspective and to the EU as a whole, with varying degrees of salience in the individual member states. The unsustainable way in which land is used for agriculture and often also forestry, along with other factors such as land fragmentation and pollution, contributes significantly to this poor state of affairs. This is not only a question of the diversity of species and habitats, but equally important is the fact that ecosystems are increasingly unable to provide the services that are essential for our existence, such as climate protection, climate adaptation and the water balance (see, e.g., IPBES 2024, Wirth et al. 2024). The trends continue to be alarmingly negative, despite numerous agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the EU Habitats and Birds Directives (see, e.g., NEOFO 2024). In a subsequent publication (Luick et al. 2025 b; submitted), the present state of global, European and German forests, their ecosystem services with regard to climate change impacts (sinks and sources of CO2) and their ability to provide resources are discussed in more detail.

The EU’s previous legislative approaches to solving environmental issues in order to fulfil the commitments it has entered into were directives (European framework laws) to the member states and political programmes such as the EU Biodiversity Strategy. However, these have largely remained unsuccessful and ineffective (see, e.g., BirdLife 2015, EC 2022c, EEA 2020, NEOFO 2024, WWF 2020; see also Section 2 above). One explanation for this is that many directives adopted in the environmental sector are only reluctantly implemented by many member states at the national level, with their content watered down and delayed. It is not uncommon for the Commission, as the ‘guardian of the treaties’, to have to initiate a so-called pilot procedure (a preliminary procedure to investigate violations of EU law) or even infringement proceedings, which repeatedly result in convictions by the European Court of Justice (ECJ). This also applies to Germany: in mid-2023, a total of 71 infringement proceedings were pending against Germany, ten of which were related to the environment alone (DNR 2023). In addition, especially in the environmental sector, the national courts frequently refer cases to the ECJ in the course of pending actions, which means that further deficiencies in the national implementation and application of European law are identified.

These are reasons why the EU Commission chose the regulatory instrument of the NRL instead of the directive (which is geared towards legal harmonisation in the Member States). The NRL offers more rapid legal enforceability, binding targets set by the EU, legal harmonisation and limits the national leeway for implementing rules. However, this restriction of national discretion has also been the cause of fierce political disputes in the run-up to legislation. Textbox 1 provides an overview of the process of lawmaking at EU level.

At the EU level, the legislative procedure – including regulations – is fundamentally different from the individual procedures of the 27 member state governments. In principle, only the European Commission has the right of legislative initiative. This means that only the Commission may submit draft legislation to the legislative organs and other bodies involved. However, other actors can request the Commission to take action:

- the European Parliament,

- the Council of the EU, also known as the EU Council of Ministers (the respective ministers of the member states),

- the European Council (the 27 heads of state and government of the EU member states plus the president of the EU Commission and the European Council).

In theory, it is also possible to introduce draft legislation via a European citizens’ initiative. EU legal acts include regulations, directives, resolutions, recommendations and statements.

- If the European Parliament and the Council adopt a regulation, as in the case of the NRL, its objectives and measures are directly binding in all EU member states. At most, the national parliaments may still have to pass laws to implement the regulation, for example, to regulate administrative responsibilities, the powers of authorities or the obligations of citizens to cooperate in the context of national legal systems.

- In the case of a directive, the parliaments of the member states have to implement this legal framework and the objectives set out in it by means of their own national law within a definite time frame. In addition to the aspects specified for enacting laws, member states must also define measures and instruments for implementation in national law.

- In principle, regulations and directives are adopted by the EU Parliament and the Council of Ministers, the two legislative bodies of the EU. While the Parliament usually makes majority decisions, decisions by the Council of Ministers often require a qualified majority. As in German law, the legislature can authorise the Commission to issue detailed provisions for implementation in delegated acts or implementing acts.

- Resolutions, too, are binding legal acts, albeit without the status of law, which, however, only address one or a few recipients (member states, corporations or individuals). They can be issued by the Council or the Commission.

- Recommendations and statements are not binding.

When the European Commission proposes an EU law to the European Parliament and the Council, the so-called ordinary legislative procedure begins, which includes one or two readings and, if necessary, a conciliation procedure and, in the case of the NRL, a third reading. The Council votes by qualified majority. The European Parliament decides by a simple majority of the votes cast at the first and third readings and by a majority of its members at the second reading.

In the voting procedure for the NRL, the definition of a qualified majority was crucial in the Council of Ministers. Since 2014, this has been defined as follows: the principle of so-called double majority applies. This means that when voting on a Commission proposal, a qualified majority is reached when two conditions are met: (1) 55% of EU countries – i.e. 15 out of a total of 27 countries – vote in favour and (2) these countries must simultaneously represent at least 65% of the total population of the Union.

Given the European Union’s ordinary legislative procedure with multiple readings, different resolutions from Parliament and the Council of Ministers, the possible failure and the drawn-out discussions, a so-called trilogue has also been possible since 2007 as a conciliation procedure to accelerate legislation. The aim of a trilogue is to reach a provisional agreement on a legislative proposal that is acceptable to both Parliament and the Council, i.e. the co-legislators. In general, a trilogue is an informal inter-institutional negotiation that can be held at any stage of a legislative procedure involving the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission. In practice, a legislative text submitted by the European Commission, but which is not capable of winning a majority in the European Parliament or the Council of Ministers, is usually amended during negotiations and deliberations in these bodies to produce a uniform provisional compromise proposal, which is then adopted individually by the Council and Parliament.

5 Positions in the debate

The Commission’s proposal for a European Nature Restoration Law with impactful content was euphorically welcomed by national, European and global institutions and organisations for environmental and nature protection. However, the largely negative assessment by institutions and organisations in the field of agriculture and commercial forestry was also to be expected in the political process. The member states represented in the Council took different positions on the NRL, as did the members of the European Parliament. Here, there were not only divergent views between the individual factions, but also within some of the factions.

Normally, the conservative pro-European factions in the EU Parliament do not flatly reject environmentally relevant laws proposed by the Commission. Many environmental laws in recent years have been constructively supported and supported by this group. In the case of the NRL, the proposal was also introduced with the support of the EPP group (European People’s Party), to which German Commission President Ursula von Leyen also belongs. This is because the NRL is a central component of the Green Deal, which is part of her government programme (see above, section 3).

The Dutch Vice President of the Commission, Frans Timmermanns, played an important role in the political arena. He was responsible for implementing the Green Deal within the Commission and was a clear supporter of the NRL, but was also blamed by conservative circles for not doing enough to find a compromise with critical and opposing groups and for undiplomatic communication. A culture of negativity towards the NRL developed, the like of which had rarely been seen in EU parliamentary proceedings. It seemed on several occasions that the project would founder on its way through the European legislative bodies. However, it should not be overlooked that there were also repeated rounds of constructive talks in which solutions were sought.

There was strong public mobilisation in all EU countries, with the pro and con camps mobilising widespread support for their respective positions. More than a million signatures in support of the NRL were collected via various campaigns and petitions addressed to the EU institutions and MEPs. Around 6,000 scientists from numerous disciplines, more than 100 companies and a broad alliance of diverse civil society organisations supported the Commission’s legislative proposal (see, e.g., Pe’er et al. 2023, 2024, Science Adviser 2023).

A distorted picture of an NRL with allegedly negative consequences emerged, mainly from agricultural and forestry associations, but also from parliamentary circles. Conflicting core beliefs, global political events, unfounded assessments and fears all combined to create an increasingly charged and sometimes absurd atmosphere. For example, Europe-wide campaigns argued (see, e.g., EVP 2022-2024, NABU 2023, SER 2023) that the NRL

- would lead to expropriations of agricultural and forestry land,

- would result in the demolition and relocation of numerous villages in order to create new wetlands or restore peatlands,

- would force agriculture to give up 10% of its productive land and the forestry industry up to 30% of forests.

- would reduce agricultural land on a dramatic scale and thus massively increase the costs of buying and leasing land,

- would lead to further massive increases in the price of food,

- in light of the war in Ukraine, the legislation has no justification and would significantly reduce food production and security of supply in the EU,

- would severely hamper the expansion of renewable energies and efforts to protect the climate and biodiversity.

These media campaigns were accompanied by massive protest actions by European farmers’ associations at national level and, in particular, by repeated demonstrations in Brussels and Strasbourg before crucial votes, which reached an unprecedented level of intensity on 26th February 2024. Eyewitnesses described riot-like scenes with massive devastation and property damage in the centre of Brussels and numerous injured law enforcement officers (see e.g. EURACTIV 2024, NOZ 2024, SZ 2024). Among the stakeholders in the legislation, only the European Federation of Hunters had a positive attitude towards the NRL and collected around 360,000 signatures in support of the NRL across Europe, the majority of them in Germany (FACE 2023). National elections, in which anti-NRL sentiment already had an impact at the ballot box (e.g. regional elections in the Netherlands in 2023), as well as the shadow of the European elections held in June 2024, also affected the parliamentary reception of the NRL in Brussels.

In this context of an increasingly populist and often one-sided public discourse, some factions of the democratic spectrum in Parliament (primarily the EPP and the Liberals), which had previously jointly supported the Green Deal, began increasingly to distance themselves from the NRL. While the EPP had long taken a critical but generally constructive approach to the draft of the NRL, a paradigm shift occurred in the context of the party congress held in Munich in May 2023. EPP Group Chairman Manfred Weber ordered the NRL to be blocked by every means possible.

In addition to their traditional proximity to agricultural and commercial forestry interests, the EPP’s negative experience of the parliamentary deliberations on the Renewable Energy Directive RED III 2022/23 (EC 2023) are a possible explanation. The EU Commission had proposed a broad ban on power plants burning wood to produce electricity due to increasing doubts about its climate neutrality. In commercial circles, this proposal was seen as political treachery that should have been stopped at the preparatory legislative phase; it led to massive pressure from agricultural, forestry and wood energy lobby groups. But there were certainly opportunistic factors in the run-up to the 2024 European elections too, with the EPP aiming to presenting themselves as representatives of the interests of conservative voters in rural areas and, in particular, farmers and forest owners.

6 The parliamentary passage of the NRL in detail

A lengthy series of votes with an uncertain outcome took place in the European Parliament. The Agriculture and Fisheries Committees, which were asked for their opinion, had rejected the Commission’s legislative proposal. The vote in the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI), which was responsible for the procedure, was now crucial for the remaining parliamentary process. The EPP had previously withdrawn from negotiations with the other factions to find a compromise and announced that it would reject the bill outright and form a possible majority alliance with the votes of the right-wing conservative ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists) and the right-wing nationalist ID (Identity and Democracy) factions.

When the EPP motion to reject the proposed law in its entirety was put to the vote on 15th June 2020, the result was a tie of 44 votes for and 44 against, meaning that the proposal was rejected. Further joint amendments by the factions of the Social Democrats, Liberals, Greens and Left were then also overwhelmingly rejected. A final vote did not take place. The parliamentary proceedings were suspended and continued on 27th June 2023.

The EPP Group’s attempts to thwart the adoption of the NRL were evident from the following. A stalemate had emerged in the Environment Committee on 15th June 2023 as a result of an unexpectedly positive vote by two German EPP members in the ENVI. In order to prevent any repetition of this at the postponed meeting and to ensure rejection, numerous EPP members were swapped for the vote on 27th June. Of the 22 MEPs now given a vote, only twelve EPP politicians were registered as full members of the committee. Of the remaining ten voters, only one person was a deputy committee member; the nine other EPP MEPs were not even named as regular deputies of the EU Environment Committee. But another surprise was to come for the EPP: the amended bill was not rejected, but referred unchanged back to the plenary for a decision.

This meant that, unusually, there was no report or recommendation for the vote in parliament. In a roll-call vote on 12th July 2023, Parliament approved the somewhat “clumsy” rough draft by 336 votes to 300, rejecting an EPP motion for rejection by 324 votes to 312. Parliament had thus decided its position by majority vote. It is noteworthy that, as in the Environment Committee, some members, particularly from the EPP, broke party discipline and voted in favour of the NRL. However, the names of the dissenters were quickly made public via social networks, and they were subjected to both stigmatisation and massive personal pressure from their own political ranks. In the meantime, the EU Council of Environment Ministers had met on 20th June 2023. There, a qualified majority (see Textbox 1) approved a ‘general approach’ to the Council’s position on the NRL (CEU 2023). After tough and controversial negotiations, an agreement on a compromise was reached in the following trilogue negotiations on 9th November. On 29th November 2023, the EU Parliament’s Environment Committee voted in favour of the NRL compromise proposal by 53 votes to 28, with four abstentions. The EU Parliament also approved the compromise proposal on 27th February 2024 with 329 votes in favour, 275 against and 24 abstentions.

7 Parliamentary showdown in the council

All that remained was for the Council to take a decision by a qualified majority. Germany, represented by Environment Minister Steffi Lemke, had always signalled its approval of the draft legislation. However, ahead of the vote in the Council of EU Environment Ministers scheduled for 25th March 2024, there was no longer a qualified majority in favour of the compromise. The representatives of eight EU member states unexpectedly withdrew their approval and either planned to vote against (including Sweden, Italy, the Netherlands and Hungary) or to abstain (Austria, Belgium, Finland and Poland). The then President of the Council, Charles Michel, reacted by removing the vote from the agenda.

A new vote took place in the Council on 17th June 2024, after the Austrian Environment Minister Leonore Gewessler (Greens) had announced her approval. The law was passed by the Council by a qualified majority, was thus adopted by both legislative bodies and was published in the Official Journal of the EU on 29th July 2024 (EU 2024). The approval by the Environment Minister, which was controversial within her Austrian government, triggered considerable conflict there. Federal Chancellor Karl Nehammer even filed a criminal complaint against her; however, in September 2024, the Austrian Public Prosecutor for Economic Affairs and Corruption (WKStA) dismissed the complaint as unfounded and no investigation took place (Der Standard 2024).

Up until the final minute, commercial forestry and industry-linked associations campaigned against the law. The umbrella organisation for European agriculture, COPA-COGECA, in which the German Farmers’ Association is one of the most important players, sent MEPs a prepared voting list with detailed recommendations for the different scenarios. In the letter, it recommended that conservative MEPs should vote in favour of amendments tabled by right-wing populist parties if a majority could not be found for a complete rejection (Arago et al. 2023). The German Forest Owners’ Association (AGDW) also strongly criticised the EU Parliament’s approval and considered it to be wrong (AGDW 2023): ’Parliament should not have approved the draft law in this form, because it would not do justice to the core objectives of the Green Deal, the limitation of climate change and species protection. The consequences of the NRL are a shortage of wood as a raw material and a significant decline in the climate performance of the forest. Other consequences are the import of wood from countries with unsustainable forestry,’ says the ADGW.

Even after the NRL was adopted, large sections of the German forestry industry and forest owners’ associations maintained their fundamental opposition. The German Association of Family-Owned Businesses in Agriculture and Forestry (FABLF), for example, spoke of a new bureaucratic edifice of diktat and regulations that counteracts the actual goal of nature conservation. The European Confederation of Private Forest Owners (CEPF) expresses the same view, calling the outcome of the vote ‘completely incomprehensible’: ’The NRL would further destabilise forests, prevent the restructuring towards climate-stable stocks and lead to a decline in the supply of wood’ (Forstpraxis 2024).

It is important to be aware of this highly charged history in the run-up to the adoption of the NRL, as it is a huge burden for the pending implementation of the NRL in the individual Member States, and particularly in Germany. Resistance to the NRL, much of which was organised by German EPP parliamentarians, is still present in the political arena. And the NRL only exists because an Austrian minister dared to make a personal decision that, although it reflected the will of the majority of Europeans, did not match that of her more powerful conservative coalition partners in government. What’s more, the NRL was adopted only in the final seconds of the term of office of the previous European Parliament and Commission.

Given the significant (conservative) shifts in power in parliament since the EU elections in June 2024, the associated policy changes and the current political line of the new EU Commission, an NRL would no longer be conceivable. It is to be expected that any further Green Deal legislation that is still pending will have only a very limited impact, if any.

8 Outlook

Is the adopted NRL now an acceptable compromise and a sufficient and binding legal basis for necessary changes in man-made landscapes, including forests? Or have the original Commission proposals been watered down to such an extent that meaningful measures are unlikely and only new bureaucracy and reporting requirements will result? In a follow-up paper (Luick et al. 2025 a; submitted), we show the practical problems that now need to be solved during implementation. It will become clear that expectations are only partially matched by what is feasible. In light of this, we develop constructive proposals for how the legally binding NRL can now be translated into implementation approaches that are acceptable to the various stakeholders.

Despite all its shortcomings, the NRL has our full support and sympathy as a legislative project. It was the best that could be achieved in an extremely difficult political situation. Nevertheless, it is important to point out its weaknesses and deficits, which can (still) be corrected when it comes to implementation. There it is vital to avoid a situation where the NRL is, on the one hand, presented as a new ‘bureaucratic monster’ by interested parties and, on the other hand, only superficial attempts are made to fulfil its basic legal requirements.

- The target set out in the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2020 of restoring at least 15% of degraded ecosystems by 2020 through voluntary national action (this would also be in line with Aichi Target 15 of the Convention on Biological Diversity) was not even close to being achieved.

- When (European) nation states and the EU urgently demand more and stronger measures for environmental and nature protection at the international level, this is not automatically matched by appropriate implementation through EU and national instruments.

- The NRL legislative process makes it very clear how important the role of non-governmental organisations and land use associations is when they provide evidence, point out practical problems and make sensible suggestions for improvement. At the same time, it must be pointed out that, as happened in the discussion process of the NRL, patently false information is used to create media-effective narratives.

- Equally important and to be strengthened is the role of science in (1) formulating and justifying the real need for action, (2) debunking fake news and (3) developing practical goals and measures, together with relevant social actors, that are appropriate to today’s challenges (such as the transgression of planetary boundaries).

- The NRL aims to integrate the goals of actively restoring nature into a comprehensive, effective strategy, particularly with regard to climate protection and land use. In doing so, it goes well beyond the sectoral goals that have been pursued to date. In the national restoration plans and their subsequent implementation, this integrative approach to the development of multifunctionally effective ecosystems and landscapes must be realised in an ambitious way. Only thus can the necessary diverse ecosystem services be appropriately fostered.

- The legal form of a regulation means that the NRL applies directly in the EU member states and does not require further national legislation.

Arago, A., Born, C.-H., Ciscato, E., Cliquet, A. + 12 authors (2023): Legal assessment explaining why COPA*COGECA's objections against the Nature Restoration Act proposal are misleading. Tilburg University, Public Law & Governance. https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/legal-assessment-explaining-why-copacogecas-objections-against-th

AGDW (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Waldbesitzerverbände) (2023): Waldeigentümer kritisieren Zustimmung des EU-Parlaments zum Nature Restoration Law. https://www.waldeigentuemer.de/waldeigentuemer-kritisieren-zustimmung-des-eu-parlaments-zum-nature-restoration-law-richtige-ziele-aber-falscher-ansatz/

BirdLife Europe (2015): Mid-term assessment of progress on the EU 2020 Biodiversity Strategy 2020. Brussels. https://www.nabu.de/imperia/md/content/nabude/naturschutz/150601-nabu-birdlife-midtermreview.pdf

BMUV (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz) (2024): Die Nationale Strategie zur Biologischen Vielfalt 2030 (NBS 2030). https://www.bmuv.de/download/die-nationale-strategie-zur-biologischen-vielfalt-2030-nbs-2030

CEU (Council of the European Union) (2023): Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration – General approach, 2022/0195 (COD). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/65128/st10867-en23.pdf

CEU (Council of the European Union) (2024): What is the state of nature in the EU? https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/state-of-eu-nature/ Dasgupta, P. (2021): The Economics of Biodiversity – The Dasgupta Review. Full Report. 610 p. (London: HM Treasury). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review

Der Standard (2024): ÖVP mit Anzeige gegen Gewessler wegen Renaturierung gescheitert – Grüne fordern Entschuldigung. https://www.derstandard.de/story/3000000236402/wegen-renaturierungsgesetz-oevp-scheitert-mit-anzeige-gegen-gewessler

Deutsche Bundesregierung (2021): Aktiv für die biologische Vielfalt – Rechenschaftsbericht 2021 der Bundesregierung zur Umsetzung der Nationalen Strategie zur biologischen Vielfalt. Berlin. https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Naturschutz/rechenschaftsbericht_2021_bf.pdf

Deutsche Bundesregierung (2023): Indikatorenbericht 2023 der Bundesregierung zur Nationalen Strategie zur biologischen Vielfalt. Berlin. https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Naturschutz/nbs_indikatorenbericht_2023_bf.pdf

DNR (Deutscher Naturschutzring) (2023): Von der Mahnung bis zur Klage: Vertragsverletzungsverfahren im Umweltbereich. Berlin. https://www.dnr.de/sites/default/files/2022-07/steckbrief.vertragsverletzungsverfahren.pdf

De Vos, J.M., Joppa, L.N., Gittleman, J.L., Stephen, P.R., Pimm, S.L. (2014): Estimating the Normal Background Rate of Species Extinction. Conservation Biology 29 (2), 452-462. DOI.10.1111/cobi.12380

EC (European Commission) (2011): Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – Our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0244

EC (European Commission) (2019): The European Green Deal – Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640

EC (European Commission) (2020): EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 – Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380

EC (European Commission) (2021a): The European Green Deal – Delivering on our targets. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_21_3688

EC (European Commission) (2021b): The EU Forest Strategy – Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0572

EC (European Commission) (2021, 2023): Better regulation: guidelines and toolbox. https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox_en

EC (European Commission) (2022a): Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration – COM/2022/304 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0304

EC (European Commission) (2022b): Commission staff working document – Impact Assessment – Accompanying the proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on nature restoration, COM (2022) 304 final, SEC(2022) 256 final, SWD(2022) 168 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022SC0167&qid=1686750707844

EC (European Commission) (2022c): Commission staff working document – Executive Summary of the Evaluation of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022SC0285 EC (European Commission) (2023): EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED 3 – Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202302413

EEA (European Environmental Agency) (2019): The European environment – state and outlook 2020, Knowledge for transition to a sustainable Europe. https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/publications/soer-2020

EEA (European Environmental Agency) (2020): State of nature in the EU – Results from reporting under the nature directives 2013-2018. EEA Report No 10/2020, 142. DOI.10.2800/088178

EEA (European Environmental Agency) (2023): Conservation status and trends of habitats and species. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/conservation-status-and-trends-article-17-national-summary-dashboards-archived

EU (European Union) (2024): Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on nature restoration and amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869 (Text with EEA relevance). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1991&qid=1722240349976

EVP (Europäische Volkspartei) (2022–2024): https://docs.google.com/document/d/1fLvhzQvcdxsvh0lJDtRbD9zOB_Ifhwx2WCskica7j2o/edit

EURACTIV (2024): EU-Naturschutzgesetz: Befürworter und Kritiker protestieren in Brüssel. https://www.euractiv.de/section/landwirtschaft-und-ernahrung/news/eu-naturschutzgesetz-befuerworter-und-kritiker-protestieren-in-bruessel/

FACE (European Federation for Hunding and Conservation) (2023): Europäischer Europas Jäger schreiben Geschichte mit #SignforHunting-Kampagne. https://www.face.eu/2023/06/europas-jager-schreiben-geschichte-mit-signforhunting-kampagne/

Forstpraxis (2024): Nature Restoration Law beschlossen: Macht der Kompromiss eine Zusammenarbeit möglich? https://www.forstpraxis.de/nature-restoration-law-beschlossen-macht-der-kompromiss-eine-zusammenarbeit-moeglich-23048

Gatti, R.C., Zannini, P., Piovesan, G., Alessi, N. + 14 authors (2023): Analysing the distribution of strictly protected areas toward the EU 2030 target. Biodiversity and Conservation 32, 3157-3174. DOI.org/10.1007/s10531-023-02644-5

Hallmann, C.A., Sorg, M., Jongejans, E., Siepel, H. + 8 authors (2017): More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS ONE 12(10). DOI.10.1371/journal.pone.0185809

HBS (Heinrich Böll Stiftung) & BUND (2025): Wasseratlas – Daten und Fakten über die Grundlage des Lebens. Berlin, 60 S. https://www.boell.de/sites/default/files/2025-01/wasseratlas2025.pdf

IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) (2019): Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 1148 p. DOI.10.5281/zenodo.3831673

IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) (2024): The thematic assessment report on interlaces among biodiversity, water, food and health – Summary for Policymakers. https://ipbes.canto.de/v/IPBES11Media/landing?viewIndex=0

Luick, R., Jedicke, E., Fartmann, T., Großmann, M, Potthast, T., Ibisch, P. (2025a): Wie wird die EU Wiederherstellungsverordnung (WVO) umgesetzt? Die WVO im Detail und Orientierungen für weitere rechtliche Verpflichtungen. Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung 57 (4), eingereicht.

Luick, R., Jedicke, E., Fartmann, T., Großmann, M., Potthast, T., Ibisch, P. (2025b): Unsere Wälder im Spannungsfeld von Klimaschutz und Ressourcenbereitstellung – Bilanzierung und Prognosen der LULUCF-Ziele und Konsequenzen für das politische, planerische und praktische Handeln. Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung 57 (5), eingereicht.

NABU (2023): EU-Renaturierungsgesetz: Spitz auf Knopf vor wichtiger Abstimmung. https://blogs.nabu.de/naturschaetze-retten/nrl-abstimmung-umweltausschuss/

NEOFO (Netzwerk-Forum zur Biodiversitätsforschung Deutschland) (2024): Post-2020 CBD Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) – Ergebnis der CBD COP-15: 23 neue globale Biodiversitätsziele bis 2030. https://www.ufz.de/nefo/index.php?de=47996

NOZ (Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung) (2024): Bauernprotest in Brüssel eskaliert – Szenen wie in „einem Bürgerkrieg“: EU-Naturschutzgesetz droht das Scheitern. https://www.noz.de/deutschland-welt/politik/artikel/bruessel-eu-naturschutzgesetz-durch-bauernprotest-in-gefahr-46539184

Pe’er, G. Kachler, J., Herzon, I., Hering, D. + 10 authors (2023): Scientists support the EU’s Green Deal and reject the unjustified argumentation against the Sustainable Use Regulation and the Nature Restoration Law. https://zenodo.org/records/8128624

Pe’er, G. Kachler, J., Herzon, I., Hering, D. + 19 authors (2024): Role of science and scientists in public debates around environmental policy negotiations: the case of nature restoration and agrochemical regulation in the European Union. Version v4, February 5, 2024. https://zenodo.org/records/10631871

Persson, L., Carney Almroth, B.M., Collins, C.D., Cornell, S. + 10 authors (2022): Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities. Environmental Science & Technology, 56(3), 1510–1521. DOI.10.1021/acs.est.1c04158

PIK (Potsdam Institut für Klimafolgenforschung) (2024): Planetary Boundaries – defining a safe operating space for humanity. https://www.pik-potsdam.de/en/output/infodesk/planetary-boundaries/planetary-boundaries Richardson, K., Steffen, W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J. + 20 authors (2023): Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances, 9 (37). DOI.10.1126/sciadv.adh2458

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å. + 25 authors (2009): Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society 14 (2): 32. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

Rockström, J., Gupta, J., Quin, D., Lade, S.J. + 48 authors (2023): Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature, Vol. 619, 102–111. DOI.10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8

Science Adviser (2023): Scientists urge European Parliament to vote for nature restoration law. https://www.science.org/content/article/scientists-urge-european-parliament-vote-nature-restoration-law

SCBD (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity) (2020): Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. Montreal, 211 p. https://www.cbd.int/gbo/gbo5/publication/gbo-5-en.pdf

SER (Society for Restoration Ecology) (2023): Legal assessment explaining why COPA & COGECA's objections against the Nature Restoration Act proposal are misleading. https://chapter.ser.org/europe/files/2023/07/legal-assessment-of-Copa-Cogeca-objections-.pdf

SZ (Süddeutsche Zeitung) (2024): Warum der Grund für die Wut der Bauern in Brüssel liegt. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/bauern-eu-agrarpolitik-klimapolitik-gruene-proteste-1.6331286

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (1992, 2011): Convention on Biological Diversity – text and annexes. https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2023): Report of the conference of the parties (COP) of the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity on the second part of its 15th meeting (Globale Biodiversitätsrahmen von Kumming-Montreal / GBF, Global Biodiversity Framework). https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/f98d/390c/d25842dd39bd8dc3d7d2ae14/cop-15-17-en.pdf

UN (United Nations) (2019): United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) – Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 1 March 2019 (RES 73/284). https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n19/060/16/pdf/n1906016.pdf

UN (United Nations) (2020): The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration Strategy. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/31813/ERDStrat.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Wirth, C., Hansjürgens, B., Dormann, C., Mewes, M. + 6 authors (2015): Inwertsetzung von Biodiversität: Wissenschaftliche Grundlagen und politische Perspektiven. Gutachten an den Deutschen Bundestag, Büro für Technikfolgen-Abschätzung (TAB). Universität Leipzig, Deutsches Zentrum für integrative Biodiversitätsforschung (iDIV), Leipzig, 252 S. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/18/037/1803764.pdf

Wirth, C., Bruelheide, H., Farwig, N., Maylin, J.M., Settele, J. (Hrsg.) (2024): Faktencheck Artenvielfalt – Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven für den Erhalt der biologischen Vielfalt in Deutschland. Oekom, München. DOI.org/10.14512/9783987263361

WWF (2020) Time is up: EU misses 2020 biodiversity targets by a long shot, EEA report shows. https://www.wwf.eu/?979916/Time-is-up-EU-misses-2020-biodiversity-targets-by-a-long-shot-EEA-report-shows WWF (2024) Living Planet Report 2024 – a system in peril. Gland, Switzerland, 94 p. https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/2024-living-planet-report

On 18th August 2024, the EU Nature Restoration Law (NRL) came into force. The NRL is an important part of the European Commission’s Green Deal project and serves to implement legally binding UN agreements for the protection of nature and the climate (such as the Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity). The draft text changed substantially in the highly controversial legislative process from its introduction to its adoption and threatened to fail on several occasions. This article describes the legislative process and the background to it from the perspective of conservation researchers. It is important to be aware of this process and background in order to understand and support the restoration plans to be submitted by the member states by 1st September 2026, which include specific targets and implementation pathways. The creation and adoption of the NRL can be attributed to a unique political window of opportunity.

Die EU-Verordnung über die Wiederherstellung der Natur. Hintergrund, Entstehung und Verlauf des Gesetzgebungsverfahrens – ein Rückblick

Am 18.08.2024 ist die EU-Verordnung über die Wiederherstellung der Natur (WVO; EU Nature Restoration Law, NRL) in Kraft getreten. Die WVO ist ein wichtiger Bestandteil des Green-Deal-Projekts der EU-Kommission und dient dazu, völkerrechtsverbindliche UN-Vereinbarungen zum Schutz der Natur und des Klimas (etwa Klimarahmen- und Biodiversitätskonvention) umzusetzen. Der Entwurfstext hat sich im überaus kontrovers geführten Gesetzgebungsverfahren von der Einbringung bis zur Verabschiedung substanziell verändert und drohte mehrfach zu scheitern. Dieser Beitrag beschreibt aus Sicht von Wissenschaftlern der Naturschutzforschung als Rückblick den Verlauf und die Hintergründe des Gesetzgebungsprozesses. Diese zu kennen ist wichtig, um die Entwicklung der durch die Mitgliedstaaten bis zum 01.09.2026 vorzulegenden Wiederherstellungspläne mit konkreten Zielen und Umsetzungswegen zu verstehen und zu unterstützen. Die Genese und Verabschiedung der WVO ist einem einmaligen politischen Zeitfenster geschuldet.

Zu diesem Artikel liegen noch keine Kommentare vor.

Artikel kommentierenSchreiben Sie den ersten Kommentar.